(See related pages)

Web exercise: Salmon Runs in the Columbia River

A Graph of Salmon Runs in the Columbia. Integrity, Stability, and Beauty of the Land In 1935, pioneering wildlife ecologist Aldo Leopold bought 32 ha (80 acres) of worn out, sandy farmland on the banks of the Wisconsin River not far from his home in Madison. Originally intended to be merely a hunting camp, the farm quickly became a year-round retreat from the city, as well as a laboratory in which Leopold could test his theories about conservation, environmental ethics, and ecologically based land management. A dilapidated chicken shack, the only remaining building from the original farm, was remodeled into a rustic cabin (fig. 1). The whole Leopold family participated in tree planting, bird watching, gardening, and exploring nature. The old farm was not pristine wilderness nor were the Leopolds merely spectators. They regarded themselves as participating citizens of the land community, seeking to restore it to ecological health and beauty. Planting as many as 6000 trees and bushes each spring, they practiced "wild husbandry," using axes and shovels to reverse the abuses of previous owners and to revitalize the land through active management, care, and understanding. "Conservation," Leopold wrote, "is the positive exercise of skill and insight, not merely a negative exercise of abstinence or caution." While building this relationship with the land-by which he meant all the plants and animals as well as the nonliving components of the landscape-Leopold mused on the ethics and meaning of conservation and the proper role of humans in nature. The first part of his much-beloved Sand County Almanac is a collection of essays about experiments and experiences at the farm. All of us, he claimed, should choose a piece of land on which we can practice stewardship and develop a sense of place. It doesn't have to be a beautiful place. In fact, it might be best to adopt a weedy, unwanted patch that needs our love and care. Both we and the land benefit from such connectedness, he maintained. Leopold's essay on "The Land Ethic" is a cornerstone of the conservation movement and one of the most eloquent statements of environmental philosophy in American nature writing. In it, Leopold wrote, "We abuse the land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect. . . . A land ethic, then, reflects the existence of an ecological conscience, and this in turn reflects a conviction of individual responsibility for the health of the land. Health is the capacity of the land for self-renewal. Conservation is our effort to understand and preserve this capacity. . . . A thing is right when it preserves the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it does otherwise." The story of Leopold's Sand County farm embodies many of the themes of this chapter. First, we survey some of the major biomes or biological communities around the world as a measure of what the components of a healthy landscape might be. Then we examine what the relatively new fields of landscape and restoration ecology say about our environment and the roles we might play in it. Finally, we look at the emerging goals of ecosystem management and some of the controversies and questions that have persisted from Aldo Leopold's day to our own about how we can and should care for nature.

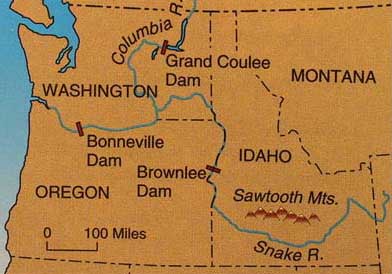

Figure 1. Aldo Leopold's Sand County farm in central Wisconsin served as a refuge from the city and a laboratory to test theories about land conservation, environmental ethics, and ecologically based land management. Until about a century ago, as many as 16 million salmon and cutthroat trout migrated every year up the Columbia River system to their breeding grounds in small headwater streams and lakes over a watershed larger than Texas (fig. 1). This was probably the greatest anadromous fish (spend part of life cycle in freshwater and part in saltwater) migration in the world. Some fish swam up to 2000 km (1250 mi) from the mouth of the Columbia on the Pacific coast to its headwaters in British Columbia or up tributary streams such as the Snake and Salmon Rivers in what is now Idaho. The fish were marvelously adapted to this remarkable journey. At least 420 separate stocks (or ecotypes) differed in the timing of their run and the subtle chemical signals they followed to find the stream where they hatched at exactly the right time for water conditions and food supplies to support their offspring. Adult salmon die after spawning and their decaying bodies nourish the ecosystem on which fry and fingerlings (young fish) will depend. The adults, each weighing as much as 220 kg (100 lbs), represent an enormous influx of nutrients into the small streams where they breed. Studies have shown that up to half of the nitrogen in riparian (stream side) vegetation in some streams comes from migrating fish. Without dead fish, the whole ecosystem is impoverished. FIGURE 6.1 Up to 16 million fish per year once migrated up the Columbia River and its tributaries such as the Snake.

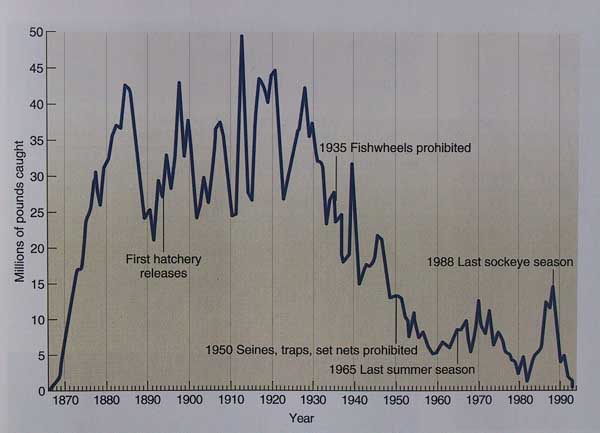

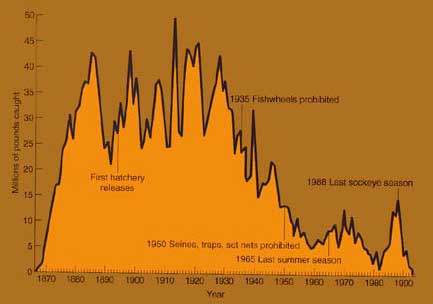

Both native people and wildlife in the Pacific Northwest depended on this prodigious bounty. For a few months every year there were more fish than anyone could eat. The runs were probably never uniform, however. For reasons that we don't fully understand, the number of fish returning from the ocean often would vary as much as 50 percent from year to year. Even now, we don't know where salmon go during the 2 to 5 years adults spend in the ocean or exactly what they eat while growing to such enormous sizes. Undoubtedly, changes in ocean temperature, circulation patterns, and food supplies caused by phenomena such as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation affect population sizes. There seems to be a 40-year cycle, for instance, when salmon runs in Alaska are high and Columbia runs are low or vice versa. Before European settlement, however, these variations didn't matter much because there were more than enough salmon for everyone. Salmon runs in the Columbia have undergone a disastrous decline during the past 80 years (fig. 2). Total numbers are down nearly 90 percent from historic highs, and only about one-tenth are now wild stocks; the rest are hatchery-reared. There are many reasons for this decrease. Overfishing by commercial operations has taken a toll. Runoff from logging, agriculture, road building, and urban areas carries warm water, sediment, and pollution that kill eggs and fry. Irrigators pump water from the river, reducing its flow. Perhaps the greatest threat to the salmon are dams that block migration. Over the past century 124 huge dams have been built on the Columbia along with 55 more on its tributaries. The river has become a chain of reservoirs. Except at its mouth, only 70 km (44 mi) of the Columbia runs free today. Fish ladders (stair step pools) help some adults move upstream but smolt (young fish), which depend on river currents to help them downstream, get lost in the slack water behind dams. Whole populations of smolt are now being barged downstream to get them past dams and reservoirs but many fail to survive anyway. Hatchery rearing of salmon began on the Columbia in the 1890s. Rather than stem the decline, unfortunately, releases of hatchery fish often have exacerbated problems. Only a few genetic strains are bred in hatcheries rather than the hundreds of wild stocks. Hatchery fish have been selected for fast growth, early maturity, and aggressive behavior. This allows them to interbreed with and outcompete native stocks. With much of their original genetic diversity gone, the fish now lack the subtle adaptations that are needed to migrate to remote streams at just the right time. At least half of the original wild salmon runs on the Columbia are now extinct and almost all that remain are in serious trouble. In a population that fluctuates as widely as salmon, it is difficult to detect patterns until long after critical events occur. If fewer fish show up this year compared to last, is it just a natural variation or an omen that something is wrong? The last big run on the Columbia River occurred in 1924 when the commercial harvest was nearly 19 million kg (42 million lbs). By the time fishwheels were prohibited in 1935, or when seines, traps, and set nets were banned in 1950, the population was already in a catastrophic decline. By 1991, when the Snake River sockeye was added to the endangered species list, only four of these fish made it to their spawning grounds in Idaho's Sawtooth Mountains. Since then, five other runs (Snake River spring and fall chinook, Umpaqua River cutthroat, and lower Columbia chum and chinook) have been added to the endangered species list while others are under consideration. Fishers and recreationists are urging the government to destroy at least four of the dams on the Snake to allow the river to run free again. Industries and residents of the Columbia River basin, who enjoy some of the lowest electric rates in the nation oppose this plan. FIGURE 6.2 Commercial salmon harvest in the Columbia River 1855-1991. By the time fishwheels, seines, traps, and set nets were prohibited, the fish were already in a downward slide.

Source: Data "Columbia Fish Runs and Fisheries 1938-93" from Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 1994 Status Report, Olympia, WA. Disappearing Butterfly Forests Every fall, in one of the most remarkable spectacles in nature, somewhere around a quarter of a billion monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) flutter southward from Canada and the United States into the mountains of central Mexico, where they spend the winter in cool, high-altitude, oyamel fir forests. Incredibly, some of these delicate insects travel up to 4000 km (2500 mi) to reach their winter refuge. Discovered by entomologists only 25 years ago, about a dozen small patches of cloud-forest about 3000 m (9750 ft) in altitude in the mountains west of Mexico City offer exactly the right conditions for monarch hibernation. With night temperatures just above freezing, and cool, foggy days, these forests allow insects to conserve energy and avoid desiccation as they await spring. The average colony contains about 20 million monarchs; some larger ones are thought to have three times this many. From November to March, tall trees in the mariposa (butterfly) forests are completely covered with bright orange and black blankets as millions of butterflies cling to tree bark and to each other, often breaking off branches with their collective weight. On sunny days when the butterflies awaken and flutter down to streams to drink, the air is filled with floating specks of color. As temperatures warm in the spring, more and more butterflies become active until sometime toward the end of March golden streams of insects pour down out of the Sierra Transvolcanica to begin their journey north once again. You can follow the migration and learn more about monarchs on the web page of Journey North, an interactive environmental science project for school children. As they move northward through Mexico and then spread out from the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic Coast, the monarchs follow spring flower emergence, sipping nectar and laying their eggs on milkweed plants providing toxins that protect caterpillars and adults from predators. Summer offspring of spring migrants live only about a month, but those hatched in the fall somehow sense the need to fly south, over a route they have never seen, to the cloud forests where they will survive until the next spring. Unfortunately, the oyamel forests on which this whole cycle depends are rapidly disappearing. Representing less than two percent of all Mexican forests, this unique ecosystem is one of the rarest and the most endangered in the whole country. Wood harvesting and fires-both accidental and deliberately set to clear land for agriculture-are the greatest threats. In 1986 a presidential decree created the "Reserva de la Biosfera Mariposa Monarca" protecting 161,100 ha (about 60 sq mi) including 5 of the 12 known monarch overwintering areas. The decree provided two levels of protection: a "nuclear" zone, in which no timber harvest is allowed, and a buffer zone, in which limited cutting is permitted. Most of the land from which the reserve was created was "ejido" or communal property, and local ejido members were never compensated properly for lost income where the logging ban was enforced. Consequently, logging-both legal and illegal-has continued in the sanctuary. Increasing numbers of ecotourists, who come to see the amazing monarch concentrations, provide some income for local communities, but tourism lasts only for about five winter months. Few peasant families can make enough money in this short season to last a whole year. Some conservationists are undertaking economic development projects to compensate residents for the costs of protecting this officially designated "threatened phenomenon" and the forests on which it depends. The Monarch Butterfly Sanctuary Foundation, for instance, is paying an ejido with land rights in the Sierra Chincua sanctuary not to log in the reserve buffer zone. This case study exemplifies issues affecting forests around the world. Growing human populations with increasing standards of living put pressures on forests that are home to threatened species. In some cases, forest destruction is the work of large, transnational corporations; in others, poor peasants cut trees to clear farmland or to make a little money from forest products. In either case, events happening in places we've never heard of affect species and essential ecological processes we consider important. Finding alternative sources of forest commodities and ways to bring about economic development that provides sustainable livelihoods not dependent on forest depletion are worldwide challenges. In this chapter we'll look at the state of world forests and grazing lands, examining how we use these lands, some problems our uses create, and ways in which threatened ecosystems can be managed more sustainably. Forestry for the Seventh Generation Until the nineteenth century, the Menominee Nation occupied nearly half of what is now Wisconsin and northern Michigan. A woodland people, the Menominee hunted, fished, and gathered wild rice. Their name for themselves, "Mano'min ini'niwuk," means wild rice people. In 1854, besieged by smallpox, alcohol, and pressure from land-hungry European settlers, the tribe was forced onto a reservation representing less than 3 percent of their ancestral lands. Although the reservation, which lies along the Wolf River about 50 miles northwest of Green Bay, WI--is in the poorest county of the state, it represents a unique treasure. The forests covering 98 percent of the land make up the densest, most diverse woodlands in the Great Lakes region and the longest-running operation for sustained-yield forestry in the country. Timber harvesting started in 1854, when 20 million board feet were cut for lumber, planks, firewood, and fence rails. Greedy lumber barons tried to gain control of valuable white pine holdings but the tribe resisted. While the rest of the state was clear-cut, burned over, and turned into farmland, the Menominee insisted on careful, selective cutting of individual trees. By 1890, the tribe had built its own sawmill and carried out the first sustainable harvest management plan in the country. When first inventoried in 1890, the 89,000 ha (234,000 acres) reservation contained 1.3 billion board feet of lumber. Today, after 107 years in which a total of 2.25 billion board feet were harvested, the forest stock has increased to 1.7 billion board feet. Ironically, the successful forestry operations almost brought about an end to the tribe. By 1959, the Menominee had accumulated a $10 million surplus. The Bureau of Indian affairs declared them too wealthy for continued protected status. Congress officially terminated the tribe in 1960, distributing trust funds and land allotments to individual tribal members. Forestry and mill operations were turned over to a private corporation, which immediately began liquidating reserves and racking up debts. Tribal leaders fought termination and successfully restored reservation status in 1973. Although the forest remains largely undivided, tribal enterprises still are plagued by debts incurred under privatization. Wise elders set up a simple forest management plan when they began operations a century ago. Rather than manage for short-term yields, as is the case for lands around them, the tribe aims for maximum quantity and quality of native species. They say, "instead of cutting the best, we cut the worst first. We're managing our resources to last forever." They have one of the few lumber operations in the country that preserves old-growth characteristics. The forest is northern hardwood type with a mixture of sugar maple, beech, hemlock, basswood, yellow birch, white pine, jack pine, and aspen. The heart of the management plan is a continuous forest inventory to determine optimum growth, species balance, ecological health, and cutting cycles. Land is divided into 109 compartments based on 11 species combinations, topography, stand history, and management goals. Two-thirds of the forest is managed for mixed species and ages, with selective cutting on a fifteen-year cycle. About 20 percent is devoted to aspen and jack pine in even-age (clear-cut) stands of no more than 12 ha (30 acres) each. Nearly 400 ha (1000 acres) of white pine utilize a two-step shelterwood program that mimics the natural fire-succession sequence by artificially manipulating the balance of sunlight, competition, and soil disturbance. Judicial use of herbicides, prescribed burns, selective cutting, and rock raking maintain optimum growth and regeneration of this valuable species, which has largely disappeared elsewhere in the Great Lakes forest. Some 300 people are now employed in the tribal forestry and sawmill operations. Logging is carried out by both Indian and non-Indian private contractors. Current harvest levels are about 30 million board feet per year. Lumber from the tribal mill is certified by the Green Cross organization as "good wood" harvested in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. As Aldo Leopold said in Sand County Almanac, the best definition of conservation "is written not with a pen, but with an axe. It is a matter of what a man thinks about while chopping, or while deciding what to chop." He was describing the kind of stewardship practiced on the Menominee reservation. In addition to welcome economic returns, the sustainable harvesting has brought them an aesthetically pleasing forest, spiritual rejuvenation, clean water, and a sense of pride in being Menominee. Ecotourism on the Roof of the World Rising dramatically from the steamy southern jungles of the Ganges River Valley to the icy peaks of the Himalayan mountains on the Tibetan border, Nepal is one of the most scenic countries in the world. Tourists savor the exotic culture of Katmandu or Namche Bazar or hike through lush mountain forests of rhododendron and pine. Offering spectacular scenery, friendly people, and low prices, this charismatic country has become a premiere destination for adventure travelers. With an annual per capita income of only $170, Nepal is among the poorest countries in the world. The phenomenal increase in visitors over the past 20 years has brought much-needed income but also has caused severe environmental degradation. Forests along popular trekking trails have been decimated to provide firewood for cooking and heating of water for the numerous wealthy outsiders, while tons of garbage and discarded gear litter popular campsites. One of the most popular Nepalese trekking routes is a three-to four-week circuit of the Annapurna Range in the center of the Himalayan Range. Crossing rushing rivers on swaying suspension bridges, passing between the 8167-m Dhaulagiri and the 8091-m Annapurna I (the seventh and tenth highest mountains in the world, respectively), this ancient pilgrim trail follows the Kali Gandaki Valley to holy shrines at Muktinath. Surmounting the 5416-m (17,769-ft) Thorung La pass north of Annapurna, hikers follow the Marsyangdi valley back to the regional center at Pokhara. First opened to foreigners in 1977, this trail now attracts over 45,000 visitors each year. Most Nepalese benefit very little from tourists who congest their villages, consume resources, and snap photographs incessantly, but the Annapurna region is different. An innovative project was launched in 1985 to alleviate the destructive impact of masses of trekkers and to maximize the income-generating potential of ecotourism. The Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP) is a 2590-km2 (1000-mi2) biosphere reserve that serves as an encouraging model for conservation and development in the Third World. Far different from Western ideals of parks composed of empty, virgin land, the ACAP is home to more than 100,000 people who continue to use resources in traditional ways. The area is divided into five different zones: intensive farming lands around the periphery, protected forest and seasonal grazing areas in the foothills, special management zones along tourist routes, protected regions with high biological or cultural richness, and wilderness areas in the high peaks. Recognizing that there can be no meaningful conservation without the active involvement of local people, fees paid by visitors to ACAP go directly to residents to manage the preserve. About $500,000 per year finances a variety of conservation, education, and development projects. More than 700 local entrepreneurs have been trained in lodge management, hygiene, and marketing. Forest guards have been hired, latrines built, trails repaired, and schools and clinics built for local people. Trekkers now are required to use kerosene rather than wood. Local tree nurseries provide stock for reforestation projects. Solar panels and water turbines provide renewable energy for both tourists and residents. The area is cleaner, healthier, and more enjoyable for everyone. This unique and successful experiment gives us a different view of the meaning and purpose of parks and nature preserves than the ideal of pristine, unchanging nature conveyed by most American national parks. It raises some interesting questions about competing needs of human and nonhuman residents and how they might be balanced sustainably. It also provides a model of how protected areas might be designed and managed in other developing countries. In this chapter, we will study the history of parks, preserves, and wildlife refuges around the world. We will examine other success stories as well as problems facing efforts to protect nature. Because of their great ecological importance, we will pay special attention to wetlands, floodplains, and coastal regions and how they need protection in many places. Northern California has had intense debates about forest management policy for many years. On one hand, many small rural communities are almost totally dependent on the forest industry for economic survival. On the other hand, as native, old-growth forests become increasingly scarce, many environmental groups call for a sharp decrease in logging on public lands, and campaign to preserve as much as possible of what wilderness is left in its original state. The Forest Service is caught in the middle of this debate, with a mandate for both environmental protection and economic production. How can it reconcile these competing demands? An experiment in community-based environmental planning in the small Sierra Nevada town of Quincy, California, has recently generated a great deal of interest and controversy. Some people praise it as an exciting model for cooperative management, while others deplore it as a fraud and a hoax designed to circumvent existing environmental controls and give away precious natural resources to local industry. Several wicked problems had led the citizens of Quincy to feel that they were facing a crisis that demanded some drastically new approaches. Decades of fire suppression had left the forest surrounding the town choked with dead trees and woody debris. In the dry climate of the northern Sierras, a catastrophic fire seemed inevitable. Calls for protection of roadless areas and old-growth-associated species such as the marbled murlet and the northern spotted owl, worried the forest products industry that it might not have a continuing supply of wood. With a single-industry economy, and timber harvest down as much as 80 percent from historic highs, Quincy, like many of its neighboring communities, felt like an endangered species itself. Attempts at dialog among the various factions in town usually ended up in shouting matches. One day in the early 1990s, three Quincy residents with very different backgrounds-a local timber industry employee, an ardent environmentalist, and a county supervisor-got together to talk about their common concerns. Agreeing to meet in the only building in town where they weren't allowed to shout at each other, the Quincy Library Group was born. As other residents joined the conversation, a consensus began to emerge about how the forest could be managed, environmental quality could be protected, and the local economy could survive. The Quincy Library Plan calls for new management plans on 1 million ha (2.47 million acres) of land on the Plumas, Lassen, and Tahoe National Forests. "Fuel breaks" created by thinning out dense sections of forest would allow harvesting of up to 24,000 ha (60,000 acres) of public land each year. In addition, another 24,000 ha of forest would be harvested to support the local forest industry. Roadless areas, riparian zones, and habitat for endangered species such as the spotted owl would be protected. Hailed as a breakthrough in innovative, cooperative planning, the Library Group's proposal was introduced in Congress by California Senator Dianne Feinstein and Representative Vic Fazio, as an experimental, adaptive management strategy. Each year of the "pilot project" the Forest Service must report on the economic, social, and environmental effects of its actions. After five years of environmental monitoring and science-based assessment, the whole plan will be reexamined. Failing to muster enough support in Congress to pass on its own, the Quincy Library Plan was attached as a rider on the 1999 Omnibus Appropriation Bill, which was signed into law by President Clinton in 1998. Environmental groups denounced both the method of passage as well as the content of the plan, claiming that it will double the timber harvest in the affected forest region, and subvert existing environmental laws. They claim it is a corporate welfare handout to the Sierra Pacific Industries, and will open the door to privatizing national forests. Interestingly, a split occurred between some national environmental groups, which opposed excess local control, and their northern California chapters, which defended local knowledge and autonomy. What do you think? Is community-based planning a recognition of the wisdom and practical experience of local residents, or simply a way to give special favors to local industry? Is this courageous innovation, or simply sleeping with the enemy? Is the fact that participants come to understand and like each other a healthy development or the beginning of a sell-out? Would it be better to maintain an adversarial stance in this case, or seek compromise? |