|  Research Projects in Statistics Joseph Kincaid,

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas City

Overview

Implementation tipsUsing real data

The first time you implement research projects in your class, you will be sorely tempted to just give the data to the students. Even after several successful semesters with research projects, you may still be visited by this demon once in a while. You should resist this temptation strongly.

The reason this temptation is so strong is that collecting data can be one of the most difficult portions of the project for the students. However that very reason is the main reason why you should resist. By helping the students through the most difficult part of true data analysis, you will be giving them not only a healthy respect for the types of issues they will encounter, but also hands-on experience working through the issues that arise in data collection. This experience will be extremely valuable throughout the project and throughout their lives as data users.

When the students implement a proper random sample of a population, they will be developing discernment skills that will help them judge whether proper randomness was used in another study they are involved in. When the students measure items on their own and have to ask themselves hard questions about rounding off the measurements, they will be developing an intuition for how rounding affects the results of a study. When the students analyze data based on a sample size that they selected, they will see first-hand the effects of sample size on the power of the statistical test.

Project schedule

There are four main principles to follow when deciding on a schedule for the project.

- Be aggressive with deadlines.

- Encourage the students to plan ahead .

- Spread the work out evenly..

- Manage for exceptions.

Be aggressive with deadlines. When setting deadlines for the various phases of the project, it is important to be on the aggressive side of reasonable. The reason for this is simple: If something needs to change, extending a deadline is a lot easier than accelerating one.

Encourage the students to plan ahead. From a scheduling perspective, this means introducing the students to the project as soon as possible so that they have as much opportunity as possible to think about the project. If you delay the initial work on the project, the students won’t have as much time to plan and their work will suffer accordingly.

Spread the work out evenly. In addition to the primary advantage of not giving the student a really bad week at some point, spreading the work out evenly helps to maintain the importance of the project in the students’ minds. This can be accomplished by having due dates every couple of weeks at the beginning when the deliverables are smaller and then spreading them out more at the end of the semester when the deliverables are larger.

Manage for exceptions. The project deadlines should appear to be very solid in the minds of the students. However, if something goes wrong, they should be flexible enough to allow the students to recover. Further, holidays and vacations, exam dates and any other special dates should be considered when putting together the schedule. I also try to allow time at the beginning of the semester for the roster to settle down a bit before making group assignments. This isn’t always possible in a short semester, though.

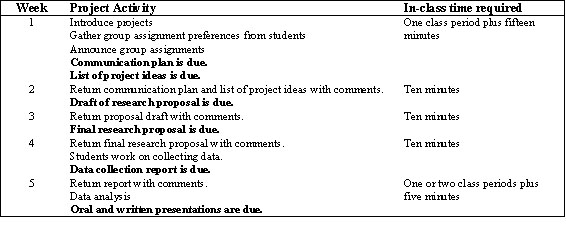

With these in mind, here is the schedule I follow in a standard 15-week semester.

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0072946814/121322/ch01_1.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (69.0K)</a>

The five minutes indicated where project components are due or returned to the student is primarily for collecting or distributing their papers. Additionally, every time I touch the project in class, I foreshadow the next component of the project to encourage the students to look ahead to their next task.

The amount of time required for the oral presentations depends on the number of groups you have. I usually spend the next to last day of the last week on oral presentations. The written presentation of results is due on the last day of class. I also use the last day to assess the individual contributions of the students.

In a 10-week class, the pace is a little faster. Because of Principle #2, Encourage the students to plan ahead, I do not recommend trimming any time from the draft of the research proposal. Instead, students should design their proposals so as to reduce the amount of time required to collect their data. Also, turn-around time on grading will need to be a little quicker. Here is my recommendation for a 10-week semester. <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0072946814/121322/ch01_1.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (69.0K)</a>

The five minutes indicated where project components are due or returned to the student is primarily for collecting or distributing their papers. Additionally, every time I touch the project in class, I foreshadow the next component of the project to encourage the students to look ahead to their next task.

The amount of time required for the oral presentations depends on the number of groups you have. I usually spend the next to last day of the last week on oral presentations. The written presentation of results is due on the last day of class. I also use the last day to assess the individual contributions of the students.

In a 10-week class, the pace is a little faster. Because of Principle #2, Encourage the students to plan ahead, I do not recommend trimming any time from the draft of the research proposal. Instead, students should design their proposals so as to reduce the amount of time required to collect their data. Also, turn-around time on grading will need to be a little quicker. Here is my recommendation for a 10-week semester.

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0072946814/121322/ch01_2.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (60.0K)</a>

In a five-week class, the main consideration is the turn-around time on grading. If the class meets daily or online, this probably is not a concern. However, if the class meets only once or twice a week, you may need to use fax, e-mail, or a website to facilitate submitting and returning project documents. Students will also need to select projects where the data can be collected quickly. <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0072946814/121322/ch01_2.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (60.0K)</a>

In a five-week class, the main consideration is the turn-around time on grading. If the class meets daily or online, this probably is not a concern. However, if the class meets only once or twice a week, you may need to use fax, e-mail, or a website to facilitate submitting and returning project documents. Students will also need to select projects where the data can be collected quickly.

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0072946814/121322/ch01_3.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (51.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0072946814/121322/ch01_3.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (51.0K)</a>Assigning groups

I find that the students work best in groups where they have some input in the group assignment process. During the first week of class, I ask the students to write down the names of others in the class with whom they would like to work on the research project. I also ask them to write down the names of anyone with whom they would not want to work with on the project. If they don’t know anyone in the class, I instruct them to write down their interest areas (such as their academic major) so that I can try to place them in a compatible group.

Group names

You may notice in the text book that one of the sample groups is named “Bebe” and one is named “Roger.” That semester, I named all of the groups after characters in the animated series Doug. I found that using a name scheme like this helped to lighten the mood at the beginning of the project. I have used the Brady kids, Muppets, Star Trek crew members, Pokémon, Animaniacs, etc. This made things a little more fun, but also helped me keep much better track of the groups.

|

|

2004 McGraw-Hill Higher Education

2004 McGraw-Hill Higher Education

2004 McGraw-Hill Higher Education

2004 McGraw-Hill Higher Education