(See related pages)

Metamorphic Facies and the Relationship to Plate Tectonics During the early part of the twentieth century, geologists in Scandinavia introduced the concept of metamorphic facies. They noted that metamorphosed basalts contained a particular set of minerals in some parts of Scandinavia, but in other regions, the minerals in metabasalts were quite different. As these rocks were chemically similar, the different mineral assemblages were regarded as indicating significantly different pressure and temperature conditions during metamorphism. Rocks having the same mineral assemblage are regarded as belonging to the same metamorphic facies, implying that they formed under broadly similar pressure and temperature conditions. The name for each facies is based on the assemblage of minerals or the name of a rock common to that facies. For instance, a metabasalt composed mostly of the minerals chlorite, actinolite, and epidote (all of which are green minerals) belongs to the greenschist facies. On the other hand, rocks of the same chemical composition (metabasalts) belonging to the amphibolite facies are largely made up of hornblende and garnet. (Do not try to remember the names of the facies or their compositions; your aim should be to understand the concept).

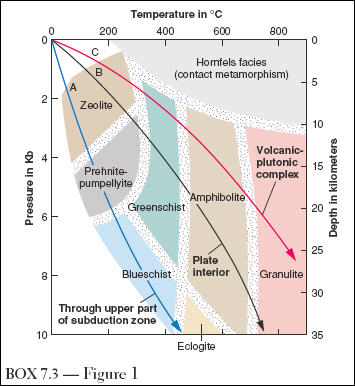

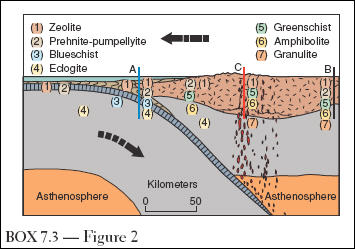

The concept of metamorphic facies is analogous to defining climatic zones by the combinations of plants found in each zone. A place where ferns, palm trees, and vines flourish corresponds to a climate with warm temperatures and abundant rainfall. On the other hand, a combination of palm trees, cactus, and sagebrush implies a hot, dry climate. By identifying the metamorphic facies of rocks presently cropping out on the surface, geologists can infer, within broad limits, the depth at which metamorphism took place. They may also (again, within broad limits) be able to determine the corresponding temperature. The concept of metamorphic facies preceded plate-tectonic theory by several decades. Although earlier geologists were able to relate the individual facies to pressure and temperature combinations, they had no satisfactory explanation for the environments that produced the various combinations. Figure 7.17, which relates the temperature of regional metamorphism to plate tectonics, may be used to infer the environment for each of the metamorphic facies shown in box figure 1. Box figure 2 shows the likely distribution of metamorphic facies across the same converging boundary as in figure 7.17. To understand the relationship, study box figures 1 and 2 as well as figure 7.17. If one were to determine the geothermal gradient represented by the three vertical lines marked A, B, and C on figure 7.17 and box figure 2, the temperatures for particular depths should plot on the corresponding arrows shown in box figure 1. Follow arrow A in box figure 1. This means that if you were able to drill vertically downward along line A, you would find, beneath unmetamorphosed rocks, rocks of the zeolite facies. At a greater depth would be the boundary between the zeolite and prehnite-pumpellyite facies. You would reach this boundary at a depth where the pressure is about 4 kilobars and the temperature is approximately 150ºC. Your drill would penetrate rocks of the prehnite-pumpellyite facies until you reached the blueschist facies. In hole B, in the interior of the plate, the progression would be from zeolite facies to prehnite-pumpellyite facies to greenschist facies to amphibolite facies to granulite facies. Hole C, in the volcanic plutonic complex, would not pass through the prehnite-pumpellyite facies but would go from zeolite facies to greenschist facies to granulite facies. |