Should We Revise the 1872 Mining Law?

Exploiting oil in ANWR

Oil and the War in Chechnya

Nauru: Mining a tropical paradise

New Madrid earthquake

What do you think? Should We Revise the 1872 Mining Law? In 1872, the U.S. Congress passed the General Mining Law intended to encourage

prospectors to open up the public domain and promote commerce. This law, which

has been in effect more than a century, allows miners to stake an exclusive

claim anywhere on public lands and to take-for free-any minerals they find.

Claim holders can "patent" (buy) the land for $2.50 to $5 per acre (0.4 hectares)

depending on the type of claim. Once the patent fee is paid, the owners can

do anything they want with the land, just like any other private property. Although

$2.50 per acre may have been a fair market value in 1872, many people regard

it as ridiculously low today, amounting to a scandalous give-away of public

property. In Nevada, for example, a mining company is buying federal land for $9000

that contains an estimated $20 billion worth of precious metals. Similarly,

Colorado investors bought about 7000 ha (17,000 acres) of rich oil-shale land

in 1986 for $42,000 and sold it a month later for $37 million. You don't actually

have to find any minerals to patent a claim. A Colorado company paid a total

of $400 for 65 ha (160 acres) it claimed would be a gold mine. Ten years later,

no mining has been done, but the property-which just happens to border the Keystone

Ski Area-is being subdivided for condos and vacation homes. According to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), some $4 billion in minerals

are mined each year on U.S. public lands. Under the 1872 law, mining companies

don't pay a penny for the ores they take. Furthermore, they can deduct a depletion

allowance from taxes on mineral profits. Senator Dale Bumpers of Arkansas, who

calls the 1872 mining law "a license to steal," estimates that the government

could derive $320 million per year by charging an 8 percent royalty on all minerals

and probably could save an equal amount by requiring a bond to be posted to

clean up after mining is finished. On the other hand, mining companies argue they would be forced to close

down if they had to pay royalties or post bonds. Many people would lose jobs

and the economies of western mining towns would collapse if mining becomes uneconomic.

We provide subsidies and economic incentives to many industries to stimulate

economic growth. Why not mining for metals essential for our industrial economy?

Mining is a risky and expensive business. Without subsidies, mines would close

down and we would be completely dependent on unstable foreign supplies. Mining critics respond that other resource-based industries have been forced

to pay royalties on materials they extract from public lands. Coal, oil, and

gas companies pay 12.5 percent royalties on fossil fuels obtained from public

lands. Timber companies-although they don't pay the full costs of the trees

they take-have to bid on logging sales and clean up when they are finished.

Even gravel companies pay for digging up the public domain. Ironically, we charge

for digging up gravel, but give gold away free. Over the past decade, numerous mining bills have been introduced in Congress.

Those supported by environmental groups, generally would require companies mining

on federal lands to pay a higher royalty on their production. They also would

eliminate the patenting process, impose stricter reclamation requirements, and

give federal managers authority to deny inappropriate permits. In contrast,

bills offered by Western legislators, and enthusiastically backed by mining

supporters, tend to leave most provisions of the 1872 bill in place. They would

charge a 2-percent royalty, but only after exploration, production, and other

costs were deducted. Permit processes would consider local economic needs before

environmental issues in this version. What do you think we should do about this

mining law? How could we separate legitimate public-interest land use from private

speculation and profiteering? Are current subsidies necessary and justifiable

or are they just a form of corporate welfare? Historic Decision to Allow Drilling

in Remote Alaska Oil Reserve July, 1998

On August 6 Interior Secretary Bruce Babbit announced the controversial

decision to authorize oil and gas drilling leases in 4 million acres of

Alaska's arctic coast. This area is part of the 23 million-acre National

Petroleum Reserve in Alaska (NPR-A), identified in 1923 as a reserve for

possible development in times of national need. At the same time, Babbit

denied leases in the wetland-rich Teshekpuk Lake area of the NPR-A, arguing

that the “biological wonderland” should be protected.

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpeg::Ak_Reds::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22970/ak_reds.jpeg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/file.gif">Ak_Reds (23.0K)</a>Ak_Reds The NPR-A occupies a region of arctic coastline adjacent to Prudhoe Bay,

the principal source of the state's oil wealth for over twenty years.

The coastal tundra, with thousands of wetlands and small lakes, provides

breeding grounds for 5 million migratory birds, representing 90 species,

including swans, snow geese, arctic loons, and many arctic coastal ducks.

The inland region of the NPR-A is home to Alaska's largest caribou herd,

the 450,000-member Western Arctic herd, as well as grizzly bears and wolves.

Environmentalists have advocated legal protection for the entire reserve,

but some have been willing to consider oil development in a portion of

the reserve in exchange for protecting the rest of the region. Development

in the NPR-A is hoped to ease pressure to open up the Arctic National

Wildlife Refuge to oil development, a proposal that was recently blocked

by President Clinton.

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::Caribou::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22970/caribou.gif','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Caribou (40.0K)</a>Caribou <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::Caribou::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22970/caribou.gif','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Caribou (40.0K)</a>Caribou

Arctic caribou herds are among the wildlife that could be threatened

by drilling in the coastal oil reserve. Interior Secretary Babbit

did deny drilling leases on the most fragile coastal wetlands. |

The compromise decision followed an 18-month environmental review and

comment period, during which Alaska's governor and congressional delegation

joined oil companies in urging the NPR-A's opening. The state is eager

to see oil development in the region because the Alaskan economy depends

heavily on oil revenue, and wells in the neighboring Prudhoe Bay area

are beginning to run dry after two decades of pumping.

Wetland Area Off-limits

Environmental groups, including the Northern Alaska Environmental Center

in Fairbanks and the Wilderness Society, decry any leasing, especially

now, when oil prices are at all-time lows, supplies are high, and there

is no current national need for further oil. In fact oil companies have

recently begun exporting Prudhoe Bay oil to Asia--a step that was strictly

denied under the region's initial development rules, which stressed the

need to preserve domestic energy security.

At the same time, denying leases in the Teshekpuk Lake area is an important

protective measure. Not only are wetlands and lakes irreplaceable breeding

grounds, they are also especially susceptible to pollution related to

oil development, including leaks in wastewater and chemical storage, in

oil pumping, and in pipeline spills and leaks. The oil industry, on the

other hand, was disappointed by the August decision to deny leases in

the coastal wetland area. The coastal plain is believed the most likely

to yield significant amounts of oil.

Exploratory drilling could begin this winter.

To read more, see Environmental Science, A Global Concern, Cunningham and Saigo, 5th ed.

US oil supplies and imports: pages 470-71

Proposals to drill in ANWR (the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge): pages

472-73

Ocean oil pollution: pages 449-50

Environmental Science, Enger and Smith, 6th ed.

Oil resources and reserves: page 145

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: page 166

For further information, see these related web sites: Environmental Impact

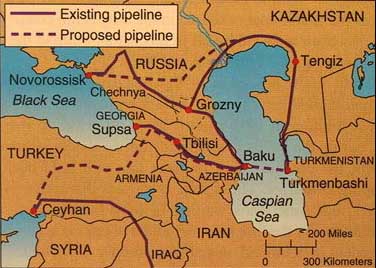

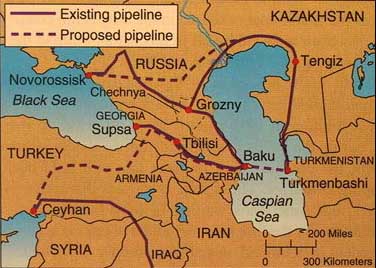

Statement information, Bureau of LandManagement Black Gold from the Caspian Twice in four years, Russian troops pounded the rebellious province of

Chechnya with bombs, rockets, and artillery in a war they can ill afford and

probably never win conclusively. Why such a ferocious assault on a tiny, impoverished

state at the fringes of their former empire? The answer is that Chechnya is

the gateway, for Russia, to what may be one the world's richest reserves of

oil and natural gas around-and under-the Caspian Sea. It has long been known that Central Asia is rich in oil. Marco Polo wrote

in the fourteenth century of "fountains from which oil springs in great abundance."

An oil boom a century ago turned Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, into a city

of instant millionaires. But the Soviet Union never put much effort into developing

Caspian oil, preferring to emphasize less politically challenging wells in Siberia.

By the 1980s, a crumbling network of leaking pipelines, rusty drilling rigs,

decaying cities, and patches of oil-soaked soil around the margins of the Caspian

showed the effects of sloppy management and neglect. When the Soviet Union broke

apart in 1991, a mad rush began as Western energy companies fought to be the

first to exploit what may be the last really big, relatively accessible oil

field in the world. Oil deposits around the Caspian Sea are thought to hold up to 200 billion

barrels, perhaps 25 percent of all the world's oil. If true, this resource would

be worth about $4 trillion at today's prices, or about 30 times as much as Alaska's

entire North Slope deposit. In addition, countries neighboring the Caspian are

thought to have enormous reserves of natural gas. Turkmenistan alone is thought

to sit on 9 trillion m3 of gas, making it the world's fourth-largest holder

of this valuable resource. In total, the Central Asian Republics may control

a quarter of the world's natural gas supply. The biggest difficulty is how to get these resources to market from their

landlocked sources. It doesn't help that the area has some of the worst weather-temperatures

ranging from -40°C to +50°C (-40°F to +122°F)-and most bellicose and unstable

political climates in the world. Regional players include Russia, Chechnya,

Dagestan, Abkhazia, Ingushetia, Ossetia, Kurdistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan,

Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Turkey, and Iran. There are more than

60 indigenous languages, and at least as many ethnic feuds in the region. Together

in the 1990s, these groups had six major wars, two presidential assissination

attempts, two coups, and countless guerrilla and bandit attacks. The shortest-and probably cheapest-route for an oil or gas pipeline from

the Caspian is across Iran to the Persian Gulf. The United States adamantly

opposed that option, however, both to thwart Iran, and because of the risk of

having additional oil passing through the vulnerable Persian Gulf. Russia has

campaigned for a route following an existing pipeline northward through Chechnya-explaining

why control of this area is so important-and then west to a Russian port on

the Black Sea. This would require tankers to pass through the congested straits

of Bosporus and the Dardanelles, and would make us dependent on Russia to keep

the oil flowing. In 1999, a contract was signed to build a 2000 km (1250 mi)

pipeline along the U.S.-preferred route from Baku, across Georgia, and then

south across Turkey to the Mediterranean Sea. An extension nearly as long would

cross under the Caspian and then run north to the Tengiz oil field in Kazakhstan.

Costing at least $4 billion (US), the pipeline will take five years to build,

and will carry about a million barrels of oil per day (42 million gal or about

6 percent of U.S. consumption) when finished. Protecting this sprawling network of vulnerable pipelines in a rugged mountainous

region of ancient but fierce ethnic, religious, and political hostilities is

a daunting prospect. Does this story suggest to you that our dependence on oil

creates odd bedfellows and difficult geopolitical problems? How far will we

go to ensure our access to energy resources? In this chapter, we will focus

on fossil fuels and nuclear power, which together supply about 97 percent of

the world's commercial energy. Chapter 22 examines some energy conservation

options as well as alternative, renewable energy sources.  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image14::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22970/Image14.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image14 (28.0K)</a>Image14 <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image14::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22970/Image14.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image14 (28.0K)</a>Image14

FIGURE 21.1 A U.S.-backed oil pipeline is proposed from Azerbaijan through

Georgia, and then southwest across Turkey to the Mediterranean. Russia prefers

a route across Chechnya to Novorossisk on the Black Sea. Mining A Tropical Paradise The tiny island-nation of Nauru (pronounced NAH-roo) in the western Pacific

is the smallest and most remote republic in the world. It also is a case study

in humanity's ability to plunder its environment. Located on the equator some

500 km west of its nearest neighbor in the Marshall Islands, Nauru has been

inhabited by Polynesian people for thousands of years. When first visited by

European explorers in the eighteenth century, the island was a lush tropical

paradise of swaying coconut palms and white coral beaches. Sailors called it

Pleasant Island, but today the name is a bitter joke. Compared to its former condition, Nauru is probably the most environmentally

devastated nation on earth. So much land has been devoured by strip-mining that

residents now face the prospect of having to abandon the whole island and move

elsewhere. What the miners sought was guano, a thick phosphate-rich layer of

bird droppings prized by industrialized countries as fertilizer. Billions of

dollars worth of this treasure have been exported, first by colonial powers

and then, since independence in 1968, by the Nauruans themselves. After a century of mining, Nauru's 7500 residents are among the richest

people in the world, but their environment has been almost totally wrecked.

Eighty percent of the 21 sq km (8 sq mi) island has been stripped, leaving a

bleak, barren moonscape of jagged coral pinnacles, some as tall as 25 meters.

With all soil washed away, almost nothing lives in this wasteland. Traveling

across it is impossible. To make things even worse, removing the vegetation

has changed the climate. Heat waves rising from the sun-baked rock drive away

rain clouds and the island now is plagued by constant drought. Not only the island is ravaged. Nauruans may be among the world's most

affluent people, but they are also among the most unhealthy, plagued by cardiovascular

disease, diabetes, and obesity brought about by a lifestyle of idleness and

imported junk food. Few islanders live past the age of 60. Since most mining

is done by imported workers, Nauruans generally lack job skills to apply elsewhere.

This case study is a sad example of how easy it is for modern technology and

lack of foresight to degrade both a society and its environment. The guano deposits are expected to last only a few more years. After that,

residents will be left with only a thin sliver of habitable coastline. Some

efforts have been made to import new soil and to restore vegetation to the desolate

interior, but attempts have been unsuccessful. It may be too late to reverse

the damage. The people may be able to use some of their accumulated trust fund

to buy another island, but will they find one as comfortable and beautiful as

what they once had? One village leader says wistfully, "I wish Nauru could be

like it was before. I remember it was so beautiful and green everywhere. We

could eat coconuts and breadfruit. It makes me cry when I see what has been

done. I wish we'd never discovered the phosphate." Could Nauru's example be a warning for all of us? Humans have a long history

of depleting resources and then moving on. Could we find ourselves in a similar

situation someday, having exhausted our natural resources but then having an

uninhabitable world? Ethical Considerations If the Nauruans appeal for help in finding another place to live, would

we be morally obligated to assist them? Do countries that bought fertilizer

from Nauru bear a special responsibility for what has happened? If we see other

examples of environmental destruction occurring elsewhere, would we be ethically

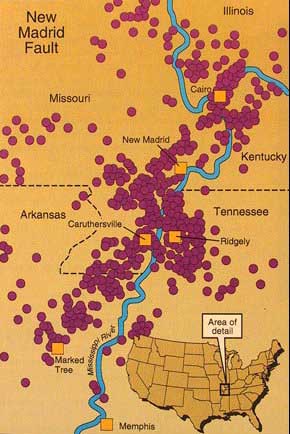

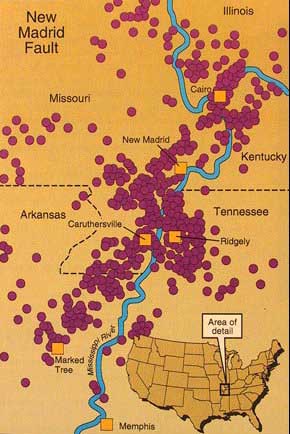

justified to try to intervene and stop it? New Madrid Earthquake In 1994, a strong earthquake (magnitude 6.6 on the Richter scale) jolted the

city of Northridge in the San Fernando Valley just north of Los Angeles and

reminded us of the dangers of geological forces. Fifty-five people died, 75,000

were left homeless, and more than 3 million people lost power, light, and heat

as buildings crumbled, electric power lines ruptured, and gas lines exploded.

Traffic was hopelessly snarled for months afterward because dozens of bridges

collapsed and highways snapped like twigs. Repairs are estimated to cost $15

billion to $20 billion. Devastating as this earthquake was, it was not by any means the largest or

most catastrophic that might occur. Geologists warn that a really "big

one" (greater than 8.0 on the Richter scale) is likely along the sound

end of the San Andreas Fault east of Los Angeles. Even more ominous is the likelihood

that the Elysian Park fault system which passes directly beneath downtown Los

Angeles, could unleash a tremor with ten times the destructive power and hundreds

of times as much loss of life and property damage as the Northridge quake. Surprisingly, the West Coast is not the only place in the United States where

a geological cataclysm might occur. People who think that earthquakes are strictly

a Californian phenomenon might be amazed to learn that the most powerful earthquake

in recorded American history occurred in the middle of the country near New

Madrid (pronounced MAD-rid), Missouri. Between December 16, 1811, and February

7, 1812, about 2,000 tremors shook southeastern Missouri and adjacent parts

of Arkansas, Illinois, and Tennessee. The largest of these earthquakes is thought

to have had a magnitude of 8.8 on the Richter scale making it one of the most

massive ever recorded. Witnesses reported shocks so violent that trees two meters thick were snapped

like matchsticks. More than 60,000 ha (150,000 acres) of forest were flattened.

Fissures several meters wide and many kilometers long split the earth. Geysers

of dry sand or muddy water spouted into the air. A trough 240 km (150 mi) long

64 km (40 mi) wide, and up to 10 meters (30 ft) deep formed along the fault

line. The town of New Madrid sank about four meters (12 ft). The Mississippi

River reversed its course and flowed north rather than south past New Madrid

for several hours. Many people feared that it was the end of the world.  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image 15::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22970/Image15.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image 15 (31.0K)</a>Image 15 <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image 15::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22970/Image15.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image 15 (31.0K)</a>Image 15

One of the most bizarre effects of the tremors was soil liquefaction. Soil

with high water content was converted instantly to liquid mud. Buildings tipped

over, hills slid into the valleys, and animals sank as if caught in quick-sand.

Land surrounding a hamlet called Little Prairie suddenly became a soupy swamp.

Residents had to wade for miles through hip-deep mud to reach solid ground.

The swamp wasn't drained for nearly a century. Some villages were flattened by the earthquake; others were flooded when the

river filled in subsided areas. The tremors rang bells in Washington, D.C.,

and shook residents out of bed in Cincinnati. Since the country was sparsely

populated in 1812, however, few people were killed. The situation is much different

now, of course. With a much larger population living in the area, the damage

from an earthquake of that magnitude would be calamitous. Much of Memphis, Tennessee,

only about 100 mi from New Madrid is built on landfill similar to that in the

Mission District of San Francisco where so much damage occurred in 1994. St.

Louis had only 2,000 residents in 1812; nearly half million live there now.

Scores of smaller cities and towns lie along the fault line and transcontinental

highways and pipelines cross the area. Few residents have been aware of earthquake

dangers or how to protect themselves. Midwestern buildings generally are not

designed to survive tremors. Anxiety about earthquakes in the Midwest was aroused in 1990 when a climatologist

predicted a 50-50 chance of an earthquake 7.0 or higher on or around December

3, in or near New Madrid. Many people gathered emergency supplies and waited

nervously for the predicted date. Although there were no large earthquakes along

the New Madrid fault in 1990, thousands of small quakes rock the area each year.

Most are too faint to be noticed by citizens, but the probability of a major

tremor there remains high. While the general time and place of some earthquakes have been predicted with

remarkable success, mystery and uncertainty still abound concerning when and

where "the next big one" will occur. Will it be in California? Will

it be in the Midwest? Or will it be somewhere entirely unsuspected? Meanwhile,

residents of New Madrid are planning emergency exit routes and stocking up on

camping gear and survival supplies. How about you? What would you do if the

ground around you began to shake? |

2002 McGraw-Hill Higher Education

2002 McGraw-Hill Higher Education