(See related pages)

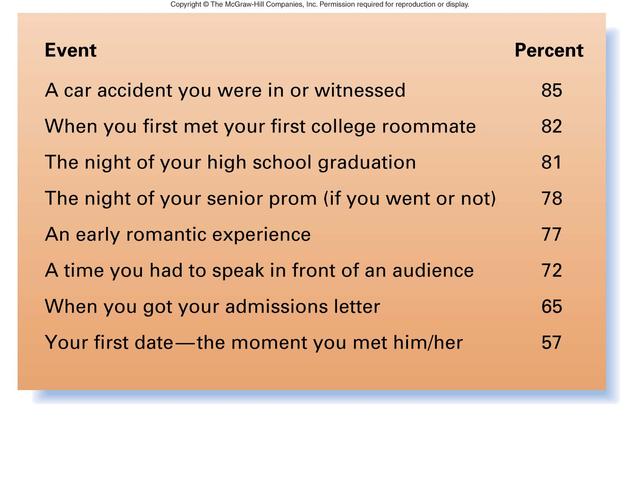

When we remember our life experiences, the memories are often wrapped in emotion. Researchers have found that emotion affects the encoding and storage of memories and thus shapes the details that are retrieved. Consider flashbulb memories. Although nationally prominent events or circumstances do create vivid flashbulb memories, the vast majority are of a personal nature. In one study, college students were asked to report the three most vivid memories in their lives (Rubin & Kozin, 1984). Virtually all of these memories were of a personal nature. They tended to center around an injury or accident, sports, members of the opposite sex, animals, deaths, the first week of college, and vacations. Students in this study also answered questions about the types of events that were most likely to produce flashbulb memories. These are the types of events that more than 50 percent of the students said were of "flashbulb" quality:

Some flashbulb memories involve emotionally uplifting experiences, as when a person remembers the positive emotional experience of high school graduation night. But other flashbulb memories are at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum and involve personal trauma. In 1890, William James said that an experience can be so arousing emotionally as to almost leave a scar on the brain's tissue. Some cases of memory for personal trauma involve a mental disorder called post-traumatic stress disorder, which includes severe anxiety symptoms. These symptoms may not appear immediately follow the trauma; in fact, onset may be delayed by months or even years. The symptoms can include "flashbacks" in which the individual relives the traumatic event in nightmares or in an awake but distracted state. They may also include difficulties with memory and concentration. Post-traumatic stress disorder can emerge after exposure to several kinds of traumatic events, such as war, severe abuse (as in rape), and accidental disasters (such as a plane crash). Stress-related hormones likely play a role in memories that involve personal trauma. The release of stress-related hormones, signaled by the amgydala, likely account for some of the extraordinary durability and vividness of traumatic memories (Schacter, 1996). Understanding the distortions of memory is especially important when people are called on to report what they saw or heard in relation to a crime. Eyewitness testimonies, like other sorts of memories, may contain errors. But faulty memory in criminal matters has especially serious consequences. In the high-profile O. J. Simpson murder trial, many people were puzzled when Simpson's housekeeper testified that his infamous white Bronco had not moved from its spot all evening. Yet Simpson's limousine driver testified that he did not remember seeing the car when he arrived late that evening. This was only one of many discrepancies in eyewitness testimony that occurred in the Simpson trial. They regularly occur in other trials as well. Much of the interest in eyewitness testimony focuses on distortion and inaccuracy in memory (Loftus, 1993). One reason for distortion is that memory fades over time. Also, unlike a videotape, memory can be altered by new information. In one study, students were shown a film of an automobile accident (Loftus, 1975). Students were asked how fast the white sports car was going when it passed a barn. In fact, there was no barn in the film. However, 17 percent of the students who heard this question mentioned the barn in their answer, indicating that their memories had been shaped by the questioner's suggestion that a barn had been in the scene. Bias is also a factor in faulty eyewitness memory. In one experiment, a mugging was shown on a television news program (Loftus, 1993). Immediately after, a lineup of six suspects was broadcast and viewers were asked to phone in and identify which of the six individuals they thought had committed the robbery. Of the 2,000 callers, more than 1,800 identified the wrong person. Even though the robber was White, one-third of the viewers identified an African American or Latino suspect as the criminal. Loftus, E. F. (1975). Spreading activation within semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 104, 234-240. Loftus, E. F. (1993). Psychologists in the eyewitness world. American Psychologist, 48, 550-552. Rubin, D. C., & Kozin, M. (1984). Vivid memories. Cognition, 16, 81-95. Schachter, D. L. (1996). Searching for memory. New York: Basic Books. |