Origin of the Idea  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origins_image.gif','popWin', 'width=70,height=90,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (1.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origins_image.gif','popWin', 'width=70,height=90,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (1.0K)</a> | 9.1 The Aggregate Expenditures Model |  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origins_image.gif','popWin', 'width=70,height=90,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (1.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origins_image.gif','popWin', 'width=70,height=90,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (1.0K)</a> | 9.2 Say's Law |

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origins_image.gif','popWin', 'width=70,height=90,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (1.0K)</a>9.1 The Aggregate Expenditures Model <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origins_image.gif','popWin', 'width=70,height=90,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (1.0K)</a>9.1 The Aggregate Expenditures Model

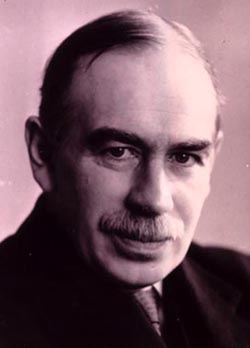

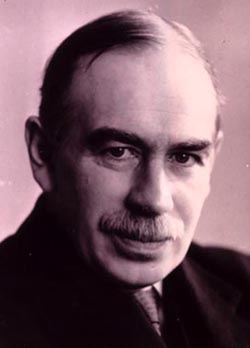

The theories of consumption and investment articulated by John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) form the basis for the aggregate expenditures model, but Paul Samuelson (b. 1915) synthesized the model. Samuelson was the first American to win the Nobel Prize in Economics.

The aggregate expenditures model is an example of Keynesian economics, and not directly the economics of Keynes (the distinction is explained below). Still, the mark Keynes left on the model is indelible.

John Maynard Keynes was, arguably, the most influential economist of the 20th century. His seminal contributions to macroeconomic theory, his philosophical shift from the conservative neoclassical mainstream in economics, and the sheer number of economists and policy-makers who bore his banner, all serve to make Keynes a leading economic figure.

Keynes was destined to a life of intellectual pursuits from the very beginning. His mother served as a justice of the peace, an alderwoman, and the mayor of Cambridge. His father, John Neville Keynes, was an accomplished logician and political economist. John Maynard Keynes studied at Cambridge under the guidance of prominent economists Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) and A.C. Pigou (1877-1959).

Following his studies at Cambridge, he became editor of the Economic Journal, and successfully managed the investments of the Royal Economic Society, its publisher, and King's College of Cambridge, as well as his own. Keynes was a speculator, but interestingly, had this to say about speculators:

|  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124320/origin09_3a.jpg','popWin', 'width=300,height=418,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (34.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124320/origin09_3a.jpg','popWin', 'width=300,height=418,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (34.0K)</a> |

Speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise. But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation. When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done. The measure of success attained by Wall Street, regarded as an institution of which the proper social purpose is to direct new investment into the most profitable channels in terms of future yield, cannot be claimed as one of the outstanding triumphs of laissez-faire capitalism – which is not surprising, if I am right in thinking that the best brains of Wall Street have been in fact directed towards a different object.(1)

Keynes was a prolific writer and a prominent social and political figure. He was the main representative of the British Treasury at the peace conference after World War I, given the power to speak for the Chancellor of the Exchequer. He was highly critical of the Paris negotiations and the eventual Treaty of Versailles, causing him to resign his position in 1919 and begin writing The Economic Consequences of the Peace, published in 1920. In this work he predicted that the reparations imposed on Germany were excessive and would lead to political and economic conditions conducive to future armed conflict. He also served as trustee of the National Gallery, chairman of the Council of the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, chairman of the Nation and New Statesman magazines, and chairman of the National Mutual Life Assurance Society. He organized the Camargo Ballet (his wife, Lydia Lopokova, was a renowned star of the Russian Imperial Ballet), and built the Arts Theatre at Cambridge.

Keynes published The End of Laissez-Faire in 1926. While not his best known work, it did clearly articulate his feelings about capitalism and establish his philosophy that government involvement was necessary to bring about long term economic security. Keynes believed laissez-faire capitalism resulted in significant inequalities of wealth, excessive unemployment, and inefficiency:

Yet the cure lies outside the operations of individuals; it may even be to the interest of individuals to aggravate the disease. I believe that the cure for these things is partly to be sought in the deliberate control of the currency and of credit by a central institution, and partly in the collection and dissemination on a great scale of data relating to the business situation…. These measures would involve Society in exercising directive intelligence through some appropriate organ of action over many of the inner intricacies of private business, yet it would leave private initiative unhindered...

Devotees of Capitalism are often unduly conservative, and reject reforms in its technique, which might really strengthen and preserve it, for fear that they may prove to be first steps away from Capitalism itself... For my part, I think that Capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight, but that in itself it is in many ways extremely objectionable. Our problem is to work out a social organization which shall be efficient as possible without offending our notions of a satisfactory way of life.(2)

Keynes' magnum opus was The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, published in 1936. Writing in response to the Great Depression and the seeming impotence of classical economic theory to provide a solution, The General Theory articulates most of the economics of Keynes that would later evolve into the theories we recognize today.

The Economics of Keynes v. Keynesian Economics

It should be noted that while Keynes' writing provided inspiration for a number of economists who would come to be known as Keynesians, many of the well-known theories bearing his name were not developed by Keynes himself. For example, the IS-LM model, a Keynesian model you are likely to see in an intermediate macroeconomics course, was the result of work by Alvin Hansen (1887-1975) and John R. Hicks (1904-1989).

- John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1936), p. 159. Reprinted by permission of Harcourt Brace and Company.

- John Maynard Keynes, The End of Laissez-Faire (London: Hogarth, 1926), p. 47-58.

Photograph courtesy of: Cambridge University Press 1985, Mark Blaug, Great Economists Before Keynes

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origins_image.gif','popWin', 'width=70,height=90,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (1.0K)</a>10.2 Say's Law <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origins_image.gif','popWin', 'width=70,height=90,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (1.0K)</a>10.2 Say's Law

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origin10_2.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (40.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073273082/124310/origin10_2.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (40.0K)</a>

As indicated in the text, Say's Law is attributed to the French economist, Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832). Born in Lyon, France, Say led a life of varied professional activities. He worked as a life insurance salesman, a journalist, a government official under Napoleon, an entrepreneur (he opened a cotton spinning mill), and finally a professor of political economy. Say declined an invitation from Thomas Jefferson to teach at the newly established University of Virginia, and instead became the first professor of economics at a French university. The interesting question about Say's Law (also referred to as Say's Law of Markets) is how much of Sa's Law we should credit to Say. This question has two dimensions to it: First, did Say develop the ideas, and second, is the modern version of Say's Law really what Say intended? Say was not the first to articulate the ideas now embodied in Say's Law. Francis Hutcheson, one of Adam Smith’s teachers, was first credited with writing about the impossibility of overproduction. Smith wrote, "A particular merchant, with abundance of goods in his warehouse, may sometimes be ruined by not being able to sell them in time, [but] a nation is not liable to the same accident." James Mill, credited with coining the phrase "supply creates its own demand," wrote in 1808 that, "If a nation's power of purchasing is exactly measured by its annual produce … the more you increase the annual produce, the more by that very act you extend the national market, the power of purchasing and the actual purchases of the nation."(1) Finally, we get to Say's remarks on the matter:

It is worth while to remark, that a product is no sooner created, than it, from that instance, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value. When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product, he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should vanish in his hands. Nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable. But the only way of getting rid of money is in the purchase of some product or other. Thus, the mere circumstance of the creation of one product immediately opens a vent for other products ...(2) The theory did not officially become known as Say's Law until John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) used the phrase in 1936, when Keynes was attempting to discredit the theory. Given Keynes’ motives, it is reasonable to ask whether Keynes represented accurately the ideas of Say. The most recent word on Say's Law comes from economist William Baumol. Despite what we "know" about Say's Law, Baumol asserts that there are still unresolved issues, regarding both substance and origin. As revealed above, Say's Law was not the creation of one individual, but was born of an intellectual dialogue that began in the late 18th century. Who created Say’s Law? In Baumol’s words, "they probably all did," (with "all" referring to not only J.B. Say, James Mill, and John Maynard Keynes, but also to classical economists such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo). William O. Thweatt, "Early Formulators of Say's Law," Quarterly Review of Economics and Business 19 (Winter 1978): 79-96. J. B. Say, A Treatise on Political Economy (Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1880), p. 134-135. [Originally published in 1803].

|

Photograph courtesy of: (c)Corbis #OCE0027 Photograph courtesy of: (c)Corbis #OCE0083 Photograph courtesy of: (c)Corbis #OCE0092 |