Application: Graph of Salmon Runs, Columbia River

Aldo Leopold: Maintaining the integrity, stability and beauty

Salmon runs in the Columbia river

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Salmon Runs::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22965/salmon_runs.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Salmon Runs (32.0K)</a>Salmon Runs <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Salmon Runs::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22965/salmon_runs.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Salmon Runs (32.0K)</a>Salmon Runs

A Graph of Salmon Runs in the Columbia. Integrity, Stability, and Beauty of the Land In 1935, pioneering wildlife

ecologist Aldo Leopold bought 32 ha (80 acres) of worn out, sandy farmland on

the banks of the Wisconsin River not far from his home in Madison. Originally

intended to be merely a hunting camp, the farm quickly became a year-round retreat

from the city, as well as a laboratory in which Leopold could test his theories

about conservation, environmental ethics, and ecologically based land management.

A dilapidated chicken shack, the only remaining building from the original farm,

was remodeled into a rustic cabin (fig. 1). The whole Leopold family participated

in tree planting, bird watching, gardening, and exploring nature. The old

farm was not pristine wilderness nor were the Leopolds merely spectators. They

regarded themselves as participating citizens of the land community, seeking to

restore it to ecological health and beauty. Planting as many as 6000 trees and

bushes each spring, they practiced "wild husbandry," using axes and shovels to

reverse the abuses of previous owners and to revitalize the land through active

management, care, and understanding. "Conservation," Leopold wrote, "is the positive

exercise of skill and insight, not merely a negative exercise of abstinence or

caution." While building this relationship with the land-by which he meant

all the plants and animals as well as the nonliving components of the landscape-Leopold

mused on the ethics and meaning of conservation and the proper role of humans

in nature. The first part of his much-beloved Sand County Almanac is a collection

of essays about experiments and experiences at the farm. All of us, he claimed,

should choose a piece of land on which we can practice stewardship and develop

a sense of place. It doesn't have to be a beautiful place. In fact, it might be

best to adopt a weedy, unwanted patch that needs our love and care. Both we and

the land benefit from such connectedness, he maintained. Leopold's essay on

"The Land Ethic" is a cornerstone of the conservation movement and one of the

most eloquent statements of environmental philosophy in American nature writing.

In it, Leopold wrote, "We abuse the land because we regard it as a commodity belonging

to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use

it with love and respect. . . . A land ethic, then, reflects the existence of

an ecological conscience, and this in turn reflects a conviction of individual

responsibility for the health of the land. Health is the capacity of the land

for self-renewal. Conservation is our effort to understand and preserve this capacity.

. . . A thing is right when it preserves the integrity, stability, and beauty

of the biotic community. It is wrong when it does otherwise." The story of

Leopold's Sand County farm embodies many of the themes of this chapter. First,

we survey some of the major biomes or biological communities around the world

as a measure of what the components of a healthy landscape might be. Then we examine

what the relatively new fields of landscape and restoration ecology say about

our environment and the roles we might play in it. Finally, we look at the emerging

goals of ecosystem management and some of the controversies and questions that

have persisted from Aldo Leopold's day to our own about how we can and should

care for nature.  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image7::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22965/Image7.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image7 (33.0K)</a>Image7 <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image7::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22965/Image7.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image7 (33.0K)</a>Image7

Figure 1.

Aldo Leopold's Sand County farm in central Wisconsin served as a refuge from the

city and a laboratory to test theories about land conservation, environmental

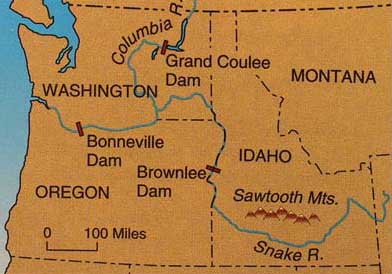

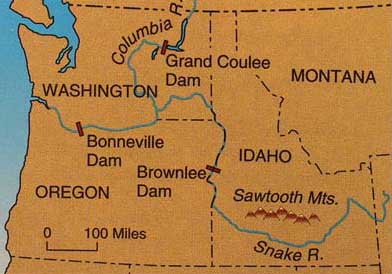

ethics, and ecologically based land management. Columbia River Salmon + Until about a century ago, as many as 16 million salmon and cutthroat trout

migrated every year up the Columbia River system to their breeding grounds in

small headwater streams and lakes over a watershed larger than Texas (fig. 1).

This was probably the greatest anadromous fish (spend part of life cycle in

freshwater and part in saltwater) migration in the world. Some fish swam up

to 2000 km (1250 mi) from the mouth of the Columbia on the Pacific coast to

its headwaters in British Columbia or up tributary streams such as the Snake

and Salmon Rivers in what is now Idaho. The fish were marvelously adapted to

this remarkable journey. At least 420 separate stocks (or ecotypes) differed

in the timing of their run and the subtle chemical signals they followed to

find the stream where they hatched at exactly the right time for water conditions

and food supplies to support their offspring. Adult salmon die after spawning

and their decaying bodies nourish the ecosystem on which fry and fingerlings

(young fish) will depend. The adults, each weighing as much as 220 kg (100 lbs),

represent an enormous influx of nutrients into the small streams where they

breed. Studies have shown that up to half of the nitrogen in riparian (stream

side) vegetation in some streams comes from migrating fish. Without dead fish,

the whole ecosystem is impoverished. FIGURE 6.1 Up to 16 million fish per year once migrated up the Columbia River

and its tributaries such as the Snake.  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image8::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22965/Image8.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image8 (23.0K)</a>Image8 <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image8::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22965/Image8.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image8 (23.0K)</a>Image8

Both native people and wildlife in the Pacific Northwest depended on this

prodigious bounty. For a few months every year there were more fish than anyone

could eat. The runs were probably never uniform, however. For reasons that we

don't fully understand, the number of fish returning from the ocean often would

vary as much as 50 percent from year to year. Even now, we don't know where

salmon go during the 2 to 5 years adults spend in the ocean or exactly what

they eat while growing to such enormous sizes. Undoubtedly, changes in ocean

temperature, circulation patterns, and food supplies caused by phenomena such

as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation affect population sizes. There seems

to be a 40-year cycle, for instance, when salmon runs in Alaska are high and

Columbia runs are low or vice versa. Before European settlement, however, these

variations didn't matter much because there were more than enough salmon for

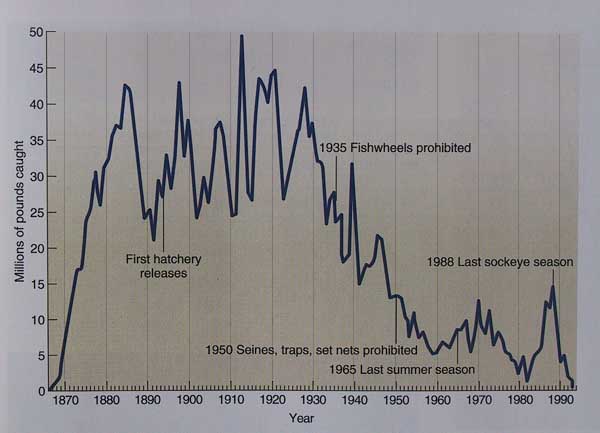

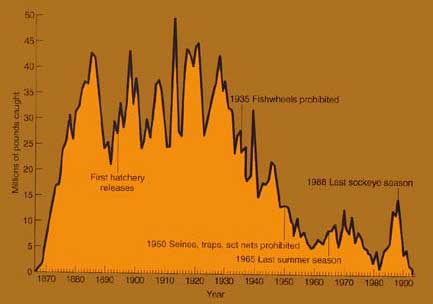

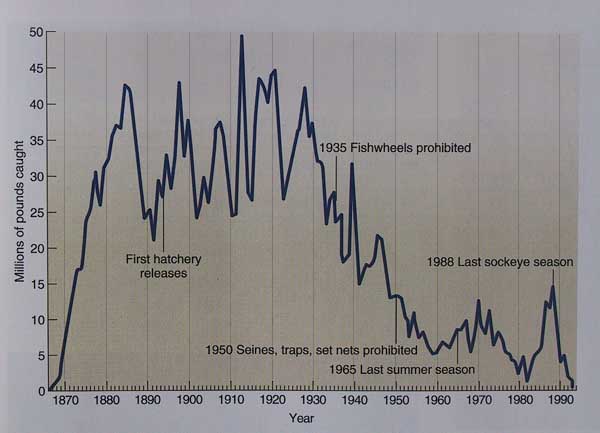

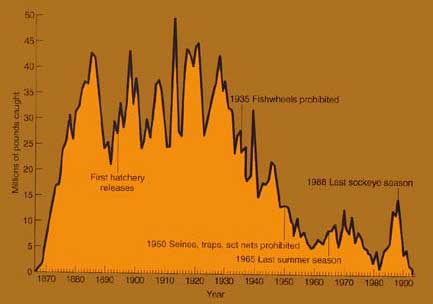

everyone. Salmon runs in the Columbia have undergone a disastrous decline during

the past 80 years (fig. 2). Total numbers are down nearly 90 percent from historic

highs, and only about one-tenth are now wild stocks; the rest are hatchery-reared.

There are many reasons for this decrease. Overfishing by commercial operations

has taken a toll. Runoff from logging, agriculture, road building, and urban

areas carries warm water, sediment, and pollution that kill eggs and fry. Irrigators

pump water from the river, reducing its flow. Perhaps the greatest threat to

the salmon are dams that block migration. Over the past century 124 huge dams

have been built on the Columbia along with 55 more on its tributaries. The river

has become a chain of reservoirs. Except at its mouth, only 70 km (44 mi) of

the Columbia runs free today. Fish ladders (stair step pools) help some adults move upstream but smolt (young fish), which depend on river

currents to help them downstream, get lost in the slack water behind dams. Whole

populations of smolt are now being barged downstream to get them past dams and

reservoirs but many fail to survive anyway. Hatchery rearing of salmon began on the Columbia in the 1890s. Rather

than stem the decline, unfortunately, releases of hatchery fish often have exacerbated

problems. Only a few genetic strains are bred in hatcheries rather than the

hundreds of wild stocks. Hatchery fish have been selected for fast growth, early

maturity, and aggressive behavior. This allows them to interbreed with and outcompete

native stocks. With much of their original genetic diversity gone, the fish

now lack the subtle adaptations that are needed to migrate to remote streams

at just the right time. At least half of the original wild salmon runs on the

Columbia are now extinct and almost all that remain are in serious trouble. In a population that fluctuates as widely as salmon, it is difficult to detect

patterns until long after critical events occur. If fewer fish show up this

year compared to last, is it just a natural variation or an omen that something

is wrong? The last big run on the Columbia River occurred in 1924 when the commercial

harvest was nearly 19 million kg (42 million lbs). By the time fishwheels were

prohibited in 1935, or when seines, traps, and set nets were banned in 1950,

the population was already in a catastrophic decline. By 1991, when the Snake

River sockeye was added to the endangered species list, only four of these fish

made it to their spawning grounds in Idaho's Sawtooth Mountains. Since then,

five other runs (Snake River spring and fall chinook, Umpaqua River cutthroat,

and lower Columbia chum and chinook) have been added to the endangered species

list while others are under consideration. Fishers and recreationists are urging

the government to destroy at least four of the dams on the Snake to allow the

river to run free again. Industries and residents of the Columbia River basin,

who enjoy some of the lowest electric rates in the nation oppose this plan.

FIGURE 6.2 Commercial salmon harvest in the Columbia River 1855-1991.

By the time fishwheels, seines, traps, and set nets were prohibited, the fish

were already in a downward slide.  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image9::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22965/Image9.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image9 (15.0K)</a>Image9 <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image9::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22965/Image9.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image9 (15.0K)</a>Image9

Source: Data "Columbia Fish Runs and Fisheries 1938-93" from Washington

Department of Fish and Wildlife and Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 1994

Status Report, Olympia, WA. |

2002 McGraw-Hill Higher Education

2002 McGraw-Hill Higher Education