(See related pages)

Dick decides to consult the online information service his newspaper uses, Lexis-Nexis®, to find material about Twain and about book censorship. A colleague in the newsroom has told Dick that she recalls reading about Twain's black butler as the inspiration for the character of Jim, the runaway slave in Huckleberry Finn. He locates a 1994 story datelined Hartford, Conn., that describes Twain's relationship with George Griffin, Twain's butler for 18 years. The home in which Twain and Griffin lived in Hartford has been made into a museum, the Mark Twain Memorial. Museum officials say Griffin, who Twain said came "one day to wash the windows and stayed for 18 years," became Twain's close friend, confidant, adviser on legal and literary matters and playmate for Twain's children. Twain wrote of Griffin as "shrewd, wise, polite, always good-natured, cheerful to gaiety, honest, religious, a cautious truth-speaker, devoted friend to the family," the story relates. The story also contains the reaction Twain and Griffin experienced when they walked into the Century Building in New York:

Dick also notes that the story includes a comment about Huckleberry Finn by the actor Hal Holbrook, who portrayed Twain on stage for more than 30 years. Holbrook says that many people misread Huckleberry Finn as racist, but that it actually satirizes prejudice. The Search As Dick gathers information, he sees that the local situation is part of a national pattern. Many communities are facing demands from parents and religious groups to remove books from school libraries and from reading lists. His eye catches a reference to the American Library Association and its report on censorship.

Banned Books Dick tries the association's Web site, which has a special category for "the 100 most frequently challenged books," www.ala.org/ala/oif/bannedbooksweek/bannedbooksweek.htm. He learns that from 1990 to 1999 there were 5,718 challenges to books. Huckleberry Finn is listed as Number 5. He notices that two other classics students read are in the first 10, Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck and The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger. Harry Potter To his surprise, the Harry Potter children's books top the list of the most challenged books in the last few years. Some parents and religious groups contend it is anti-family and has occult and Satanic themes. This seems strange to Dick. His niece and nephew are big Harry Potter readers, and his sister mentioned them to him a few weeks ago. She said she enjoyed them as well. He finds a reference to a town in Michigan, Zeeland, whose schools superintendent banned Harry Potter classroom readings, required parental permission to check then out of the library and forbade the order of further books from the series. A school teacher and a parent organized a protest and forced the superintendent and the school board, which had concurred in the superintendent's directives, to backtrack. Another news story he picks up, datelined Memphis, reports that two Catholic schools have banned the Harry Potter books. The schools asserted that the books send a message that is idolatrous. More material. He mentions this to a newsroom colleague who tells Dick that that he heard on the radio that a bishop or some church official overturned the banning and said the books were fine for children. Dick will have to verify that. The more he digs, the more Dick sees that the story he had hoped to write will take time to develop. No great rush, his editor tells Dick. "Just make sure to get all sides." They agree he will write a story for the next day's newspaper and then do an extensive takeout as soon as he can gather background and conduct interviews, possibly for this Sunday's paper. He sets to work on the story before him. He wants to include as much background as possible in this first piece rather than simply rewrite the organization's press release. Writing the Story He has an hour before his first deadline and decides he had better start writing:

Too long, he thinks. Dull. Maybe he should try a more dramatic lead:

Too sensational for this kind of story, he decides, and discards this lead. Another couple of tries, and he hits on something he likes:

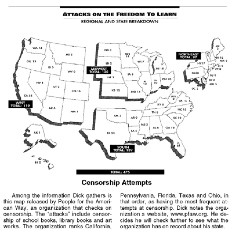

Dick realizes he will need to put the reaction of educators up high in his story and that he must quote extensively from the association statement so that readers have the full flavor of the group's anger. "Too bad," he says to himself, "we didn't have a reporter there." Then he would have something to work with—the sense of outrage, rebuttals. He puts aside the luxury of speculation and settles down to more writing. More Background After he has written his spot news story, Dick returns to his search for more information about book banning and Mark Twain. He is uncovering a treasure trove of material. Mark Twain's Generosity Dick locates a New York Times story about the discovery of a letter that Twain wrote in 1865 to the dean of Yale Law School. In it, Twain offered to provide financial help to one of the school's first black students. "I do not believe I would very cheerfully help a white student who would ask benevolence of a stranger," Twain wrote, "but I do not feel so bad about the other color. We have ground the manhood out of them,—the shame is ours, not theirs—we should pay for it." Twain subsidized the student until he graduated in 1867. Another story quotes the American Library Association's finding that more than a thousand attempts had been made to ban or restrict book usage in public schools in the 1980s. School book censors were even more active in the 1990s. Dick reads a story that reports that in the past year there were 475 incidents in 44 states in which attacks were made on schools and libraries because of the materials in their classrooms, on their reading lists and on their shelves. The censors, he learns, were successful 41 percent of the time in removing or restricting the materials they challenged. Book Banning Unconstitutional He finds a U.S. Supreme Court decision in a Long Island, N.Y., book banning. The Court upheld an appeal against book banning. Dick calls up the story from the database. The school board of the Island Trees Union Free School District had removed nine books from the shelves of junior and senior high schools on the grounds they were "anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic and just plain filthy." Down These Mean Streets was one of the banned books. The Arizona Case He also finds a story about an Arizona mother who sued the Tempe Union High School District because her daughter was required to read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and William Faulkner's short story "A Rose for Emily" for English class. The mother complained the novel and the story created a racially hostile environment because of the language used. In the January 1996 suit she asked that her daughter be exempted from the required reading. The suit finally ended up in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and in April 2001 the court unanimously decided against the mother. It ruled that while some language in the reading matter could be considered offensive, letting parents decide required reading matter on a student-by-student basis could lead to infringement of the First Amendment. "It is simply not the role of the courts to serve as literary censors or to make judgments as to whether reading particular books does students more harm than good," Judge Stephen Reinhardt wrote. Dick finds that the case has been covered intensively by the Tribune in Mesa, Ariz., and he decides he will check the paper's archives, www.aztrib.com. He will use this court case and any other material he can dig up for his Sunday story. Still More He now has a pile of notes for his Sunday story. He notices that in the list of the most frequently challenged books in the decade 1990-1999 there are many books considered classics. He estimates a third of the books are by authors on reading lists in schools. Among the authors whose books were banned are: John Steinbeck, J.D. Salinger, Aldous Huxley, Maya Angelou, Kurt Vonnegut, Roald Dahl, Maurice Sendak, Toni Morrison, Margaret Atwood, Harper Lee, Richard Wright, Alice Walker and J.K. Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter books. Are students reading these authors? he wonders. What do they think of banning books? Dick puts his notes aside and heads for the parking lot. He will drive to a luncheonette near the high school and find out. He knows the place to be a student hangout.

At the Busy Bee Dick takes a stool at the counter and orders a pizza and a soft drink. Around him, students are talking about a basketball game. Gradually, Dick eases into the conversation. He remarks that the team will have its work cut out for it next week. The students agree. In a short time, he is chatting easily with three boys. He slowly turns the conversation from sports to school work and asks them about the books they read for English classes. He asks if any one has been assigned Huckleberry Finn. One student says he has read the book on his own. Dick decides that this is the time to identify himself. He asks the student for his reaction to the book and then tells him about the association's action. One of the boys calls over some other students in a booth nearby, and soon several students, both black and white, are chatting with Dick. He lets them talk. He does not take out his notebook. He wants them to speak freely. He trusts his memory for this part of the discussion. One student says, "Maybe there are some bad things in those books. But maybe censorship is worse." The others agree. Dick takes out his pad. "That's interesting," he says. "Mind if I jot that down here?" They go on talking, and Dick quickly writes down what he has stored in his memory as he tries to keep up with the running conversation. He asks some students for their names. He would like to use them in his piece, he says. He knows that readers distrust the vague attribution to "a student." Back in the newsroom, Dick tells his editor about his chat with the students. The editor suggests Dick use the material as the basis for his Sunday interpretative piece. He and Dick discuss other people to interview. "Maybe you'd better talk to some of the people over at the university," the editor suggests. "They can tell us about efforts to condemn or censor important works." And here we take our leave of Dick. If you think you have enough information for a story, go ahead. |