(See related pages)

Sports has not been in the forefront of social change. Slow to admit minorities on the playing field and women in the press box and locker room, sports can look back only in sorrow at its behavior. This history is part of the sportswriter's background knowledge.

The 1964 season ended with the Cardinals, heavily dependent on black players, defeating the white New York Yankees in the World Series. When Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, and 11 weeks later when Larry Doby began playing for the Cleveland Indians, the color line in both major leagues was breached. Robinson and Doby had to endure race baiting, not only from fellow players but from fans as well. Pitchers threw at them, teammates would not talk to them. On the road they had to eat separately in some cities, room in different hotels. Fans shouted insults at them, and some threatened to shoot them. Jimmy Cannon wrote of Robinson, "He is the loneliest man in sports."

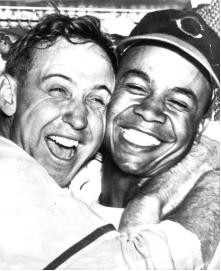

Robinson The St. Louis Cardinals were especially vituperative. In one game with the Dodgers, Enos Slaughter was an easy out but went out of his way to spike Robinson across the calf. Robinson quietly endured the taunts and the spikings and the beanballs. But as he settled in, he became more aggressive. In 1949, as Slaughter was coming into second on what would have been a routine double play, Robinson took the throw from the shortstop and instead of relaying it to first, he planted the ball in the mouth of the sliding Slaughter. Slaughter got to his feet slowly, his mouth bloodied, teeth broken. He turned and slowly walked to the Cardinal dugout. Doby Unlike the National League, in which many teams actively sought out the best young black players, the American League was slow to integrate. In his book October 1964, David Halberstam quotes the Yankees general manager telling the team's top scout, "I don't want you sneaking around down any back alleys and signing any niggers." This was the scout who when he worked for the Dodgers had endorsed the signing of Jackie Robinson. When Doby came up to play for the Cleveland Indians and was introduced to his teammates, some refused to shake his hand.

Bill Veeck, the owner of the Indians, said he received 20,000 letters after signing Doby, "most of them in violent and sometimes obscene protest." Unlike Robinson, Doby had little experience with prejudice until he became a major leaguer. Veeck said that the bigotry Doby faced made him unable "to realize his full potential. If Larry had come up just a little later when things were better, he might have become one of the greatest players of all time." A friend who later pitched for the Dodgers said Doby played under "so much pressure—from slurs to death threats—that he had to suppress some of his flair." But, like Robinson, Doby triumphed. He spent 13 years in the majors, hit 253 home runs and had a.283 career batting average. He played in six All-Star games. Robinson and Doby are in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

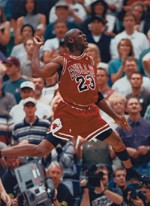

Basketball Black players dominate basketball. It wasn't always that way. In fact, basketball was as discriminatory as baseball for many years. Putting black players on the court was unusual—and frowned on. In 1963, the Loyola University of Chicago starting basketball team had four black players. They and the one white starter played the entire 45 minutes against Cincinnati in the NCAA finals. Loyola won in overtime 60-58. The coach, George Ireland once remarked, "A lot of these coaches hated the way I used so many blacks. They used to stand up at banquets and say, 'George Ireland isn't with us today because he's in Africa—recruiting.'"

Ten of the 12 El Paso players, who were recruited from Chicago, New York and Detroit, graduated. And a few years after the tournament, Rupp began to recruit black players. Haskins was admitted to the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1997. Major Impact Since Robinson's day, blacks have been the dominant figures in many sports. In baseball, over the recent dozen years, 22 of the 24 National and American League stolen-base leaders were black, as were most of the batting champions. Every rushing leader in the National Football League since 1963 has been black, and in the National Basketball Association only a few white players have led the league in scoring since 1960 and only two in rebounding since 1957. Today, blacks make up 25 percent of baseball rosters, 40 percent of the players in the National Football League and 80 percent of the players in the National Basketball Association. Although they make up only 6 percent of the college population, they account for more than 20 percent of all college athletes, more than 40 percent of the football players and about 60 percent of the basketball players. 'Glass Ceiling' While the race barrier was long ago lifted for athletes, it remains firmly in place for coaches and sports directors of the major college football teams. Although more than 50 percent of the Division 1-A football players are black, less than 3 percent of the head coaches and 4 percent of the sports directors are black. In college basketball programs, where the great majority of the players are black, about a fifth of the coaches are black. Women: Players, Reporters

Today, women engage in many intercollegiate sports, and women's basketball is a big TV draw, both the collegiate and the professional varieties. Women make up 37 percent of the athletes who compete in major college sports programs. Of the more than $500 million in athletic scholarships awarded by Division I teams, women athletes received 38 percent. Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination at schools and colleges that receive federal funds, requires the institutions to meet a "substantial proportionality test," one of three criteria that determine compliance with Title IX. The test requires institutions to match the percentage of female athletes with the percentage of female undergraduates. In practice, a school is complying if the percentage of female athletes is not more than 5 percentage points less than the percentage of female undergraduates. In the Press Box When Lesley Visser graduated from Boston College in 1976, the Boston Globe assigned her to cover the New England Patriots professional football team. She was the first female beat writer in the National Football League. After a Patriots game with the Pittsburgh Steelers, Visser waited outside the Steelers locker room to interview quarterback Terry Bradshaw. When Bradshaw spotted her with her notebook, he automatically took it from her and signed his name. Today, the editors of half a dozen major newspaper sports departments are women, and they are seen on all the major TV sports shows. Women are assigned to cover all the major sports on a regular basis at the college and professional level. But the transition for women from the sidelines was not easy. "I think women belong in the kitchen," said the owner of the San Francisco 49ers football team, Edward DeBartolo, Jr. He was commenting after a federal judge ruled that the National Football League team had to grant equal access to its locker room to a female sports reporter for The Sacramento Bee. Many athletes did not want women in locker rooms either. Two incidents symbolize the change. One occurred in the locker room of the New England Patriots after a football game; the other in a Chicago White Sox lounge, again after a game.

With the Patriots Linda Olson is covering the Patriots for the first time, and after the game she asks a player to go to the media room for an interview. "No," he says, "come over here to my locker and we'll talk." "As we sat on the bench in front of his locker, the prank began," Olson recalls. She said players "approached me, flashed their genitals and tried to get me to look while other players egged them on." They dared her to touch their genitals and made lewd comments. "Is this what you want?" one player yelled repeatedly. Olson's newspaper did not report the incident, but the Boston Globe did, and a firestorm erupted. Sports reporters, women's groups and others were outraged. Blaming the Victim But the Patriots owner Victor Kiam called Olson a "classic bitch," and during home games Patriots fans threw trash at her. When she went on to cover Celtics basketball games, the anger continued. She said she came home after covering a practice "to find the words 'Leave Boston or die' written in red spray paint on my living room walls." She had to change her telephone number many times because of calls "threatening to mutilate me for what I had done," she recalls. Hustler magazine ran a cartoon showing Olson being gang-raped by football players. She was attacked on the road by a man who punched her in the face. Olson decided to accept an offer to cover sports in Australia to get away from the anger and harassment. In an article six years after the 1990 incident, she recalls, "Lives were changed irrevocably because of those few minutes in the locker room. The general manager lost his job, the coach lost his job, all but one of the players involved is out of the NFL. Kiam had to sell the team, and I moved to Australia, the point on the map that was farthest away."

And Today? So much for history. Almost. There are still minor skirmishes. But the women give back as much, or more, as they are given. Suzyn Waldman, who covers sports for WFAN, says baseball players are among the worst, basketball players the best. After a baseball game, Waldman was bothered by a baseball player. "I told him, 'Brad, if you spent less time hassling women and more on baseball you wouldn't have done eight years in the minors.'" Tracy Dodds, assistant sports editor of The Orange County Register and national president of the Association of Women in Sports Media, was confronted in a locker room interview by a naked athlete who, she said, "presented his pride and joy" to her and asked, "Do you know what this is?" Her reply: "It looks like a penis, only smaller." Most athletes no longer care whether they are interviewed by a male or a female sportswriter. The story is told about a female sportswriter in a San Diego team's locker room following a game. As Randy Smith started to pull off his uniform, a teammate cautioned him, "Randy, there's a lady in the room." Smith replied, "That's no lady. That's only a writer." |