(See related pages)

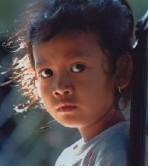

Cherie Diez Here are some excerpts from the four articles that Thomas French wrote about Mari and the other children: Out on the playground again, she walks up to one of the teachers on the bench. Her face is tight. She is on the verge of exploding with tears. "I hurt my hand" The teacher—her real name is Peggy Chlapowski, but the kids call her Mrs. Chip—looks into Mari's eyes. "You did? Well, then you can sit on my lap. Can I give it a kiss?" Mari nods and accepts the attention. A few minutes later, she jumps off Mrs. Chip's lap and rejoins her friends on the swings. But she could be back any second, ready to cry again. Her parents are from Vietnam, but they lived in a southwestern province where many of the people originally came from Cambodia, just across the border. Though they speak Vietnamese, their first language is Cambodian. The parents grew up in the same village and were married very young. Mari's father, Linh Truong, was a farmer who worked in the rice paddies. But as the years passed, he grew weary of trying to raise his family under the Communists. So he and his wife, Soi Lieu, gathered their five sons—Mari was not yet born—and fled to Thailand. They walked most of the way, hundreds of miles across the breadth of Cambodia, until finally they reached a refugee camp on the Thailand-Cambodia border. They stayed in refugee camps for two years; Mari was born in one of the camps in March 1990. Early the following year, the Truongs were granted permission to come to the United States. Three years later, the family is renting a home in St. Petersburg, eking out a living. Mr. Truong works in restaurants, washing dishes and helping with the cooking. Soi Lieu is at home, fighting a difficult battle with leukemia. For months now, the illness has rippled through the family. Soi Lieu is in and out of the hospital. When she is at home, she is often confined to bed. Because the family has little money, her care is provided through Medicaid. Mr. Truong is struggling to raise Mari and her five older brothers. The children are beside themselves. One of the boys, in what appears to be a sympathetic response to his mother's suffering, has lost most of his hair. The teachers do not know much about Mari's mother. Soi Lieu has been strong enough to visit the school only a couple of times. Like many of the Asian parents who come to the preschool, she stayed at the classroom door and did not venture inside. She said very little. And it was obvious that it was draining for her to be there, even for a few minutes. She was extremely thin, weak, washed out; although still in her 30s, she appeared to be fading before their eyes. That was months ago. Now, the teachers are told that Soi Lieu's condition has worsened. And as she has deteriorated, so has Mari. She has become distracted and moody; if even the smallest thing goes wrong, she breaks down. As the weeks go by, she seems to be disappearing inside herself. One day, exhaustion overtakes her. It happens on the bus ride home. Early every morning, a school bus—provided by contract with the Pinellas County school system—travels around St. Petersburg, picking up Mari and other children at stops near their homes and then taking them to the preschool. At the end of the school day, the bus takes them home. But on this day, Mari does not get off at her stop. The bus driver goes through her route, dropping off the children. When the driver is finished, she takes one more look around and makes a startling discovery. In her seat, out of sight, is Mari. Worn out beyond belief, she has curled up and fallen fast asleep. 2. One Monday, the children come to class buzzing with news. It is Mari, they say. She has been in a wedding. She is married. The teachers investigate. The barriers and the cultural gaps make it difficult to piece it all together, but when they press the children for information, they discover that in fact Mari and a boy at the preschool did stand together in some sort of ceremony over the weekend. The boy wore a suit. Mari wore white formal dress and a veil. Out on the playground, Mrs. St. Clair finds the boy and asks him what happened. She comes back shaking her head. "He said he married Mari," she says. "Mari will be his wife." In the days that follow, as more details find their way to the school, the teachers discover that the truth is a bit more complicated. There was a wedding over the previous weekend, but it was not between the children. The person who got married was actually the boy's mother, a close friend of Mari's mother. Mari served as a flower girl; the boy was the ring bearer. Still, there is something to the rumors. Mari's mother, it turns out, has hopes for this boy and her daughter. Soi Lieu comes from a country where arranged marriages are common. She likes this boy and respects his family. And although nothing formal has been declared or arranged, she has made it clear that she would be pleased if one day her daughter and the other woman's son united the two families through marriage. When Mari and the boy stood together at the wedding, dressed like a young bride and groom, they symbolized Soi Lieu's hopes. Mrs. Crow understands what is happening. It's the leukemia, she says. Mari's mother knows she will not be here to see her daughter become a woman. So she is squaring things away, making plans, attending as best she can to the details of a future she will not live to witness. The teachers sit on the bench under the tree, thinking through the implications. Not far away, Mari and the boy from the wedding play with their friends, running across the playground toward summer and beyond. 3. On Monday, Aug. 22, Vanessa Petrie pays another visit to Mari's house. She knows that Soi Lieu is back in the hospital, suffering from severe headaches and dizzy spells, and so she comes to see the family almost every day now. That afternoon, when Mrs. Petrie arrives, one of Mari's oldest brothers sees her and comes to the front door. "I need to check on how things are going," she tells him. "How's your mother?" The boy looks at her. "My mom died," he says. There is no expression on his face. He is obviously in shock. The whole family is in shock. Just a day or so ago, Soi Lieu was strong enough that people at the Bayfront Medical Center were talking about discharging her. But then, late on Sunday night, she apparently suffered another dizzy spell and fell. A few hours later, her heart stopped. Mrs. Petrie almost can't believe it herself. She knew Soi Lieu was close to the end, but she had hoped that the family would have a little more time to prepare themselves. She goes into the house to pay her condolences. She finds Mr. Truong in the living room, rocking on the floor. A devout Buddhist, he has already put up an altar to his wife, decorating a corner of the room with one of her photos, a bowl of flowers and some candles and incense. Now he sits before the altar, sobbing. Mrs. Petrie tries to comfort him. But the grief floods out of Mr. Truong, the words spilling forward in a numbing rush. "My wife was sick. She was in the hospital. She fell down. The blood in her head made her die. I am so sad. I am so empty." Tears welling in her own eyes, Mrs. Petrie sits on the floor with him. Mari comes up and sits beside her, clutching tightly. "My mom is dead," she says. But it clear that Mari does not comprehend what these words mean. She knows that her father and brothers are sad, that a call came from the hospital that morning, that the word "dead" has been uttered. But she does not know what the word means. How could she? Mrs. Petrie looks at her and realizes: Mari is waiting for her mother to come home. 4.

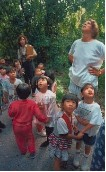

In those first weeks of the new school year, Mari Truong wanders in a trance. She sings when she is supposed to sing, she colors and paints, she joins the other children in the playground. But there is no joy in any of it, no energy or spark. She is going through the motions of being a little girl. One morning, Mrs. Chip takes Mari and her classmates outside to plant some flowers. It's a gorgeous day, with deep blue skies and just the hint of a breeze, and most of the children are excited to be doing something new. Mrs. Chip digs a row of tiny holes in the dirt beds that line the sidewalk beside the preschool. Then she taps seeds of sweet alyssum from thin packets into the children's hands and shows them how to place the seeds in the holes. When her turn comes, Mari holds the alyssum seeds in her open palm. She does not move to plant them. Instead, she stares at the ground, fixing her eyes on the row of freshly dug holes. Her face is furrowed, her body so still she seems to be holding her breath. Mari has left them. She has retreated somewhere. Inside herself. But where? Sometimes in class, when her friends are busy playing with dolls and fire trucks, she will suddenly look up and announce that her mother is dead. Is that what's going through her mind now? As she holds the seeds, is she thinking of her mother? These are not questions easily asked of a four-year-old child. Mrs. Chip sees her standing there and comes over to help. "Mari," she says, "You need to spread them over here." At the sound of her teacher's voice, Mari returns. She crouches down and puts the seeds into the hole. But then she freezes again, looking at them in the dirt. "Now you know what we have to do?" says Mrs. Chip. "We have to cover the seeds." Mari does not move. "Come on, Mari," Mrs. Chip says, speaking gently. Mari finishes packing the soil and stands up. Still staring at the ground, she wipes the dirt from her hands. In the classroom next door, they are starting at square one. Mrs. Crow and Mrs. St. Clair are struggling with the three-year-olds who are new to the Southeast Asian Preschool in St. Petersburg. Most of these children understand almost no English; many are terrified at being away from their homes. The teachers read them stories, teach them songs, ask them questions. The children just gaze back at them. The teachers show them how to sit in a circle, raise their hands, form a line. The children say nothing, struggling to understand what they are being asked to do. Out on the playground, one girl is so unnerved that she tries to escape, bolting toward the street. When the teachers bring the children juice and graham crackers for their morning snack, one of the other new students—the boy who tried to get off the bus on the first day while they were traveling on the interstate—stands dazed at the table, ignoring his food. When Mrs. Crow calls his name, trying to see if he's okay, the boy does not reply. He looks away. "It's gonna be a long year," Mrs. Chip says. During the opening days of the new semester, in the fall of 1994, the teachers sometimes struggle just to learn the children's correct names. A Cambodian boy in the younger class shows up at school without his enrollment papers. When the teachers ask him his name, he does not understand. So Mrs. Crow goes to the other classroom, where the four-year-olds are working with Mrs. Chip, and finds Piarun, a boy who speaks both Cambodian and English. She takes Piarun back to the mystery child. "Would you ask him in Cambodian what his name is?" she asks Piarun. Piarun looks up at the teacher. "I don't know," he says. "I know you don't know," Mrs. Crow says patiently. "But in Cambodian, would you ask him, ‘What is your name?'" Piarun turns to the boy. They exchange a few words, and then Piarun turns back to Mrs. Crow. "Phi," he tells her. Most people, when they first hear about the Southeast Asian Preschool, are amazed that Mrs. Crow and the other teachers are able to communicate at all with their students. They are particularly surprised that the teachers do not know any Asian languages. But that would be almost impossible, the teachers point out, since their students come from three different countries with three different languages. To speak to these children in their native tongues, the teachers would need to know Vietnamese, Cambodian and Laotian, as well as dialects of each language. When they are asked about this subject, Mrs. Crow and the other teachers respond, as politely as they can, that their job is not to learn the children's languages. Their job, first and foremost, is to teach the children the language of their new country. The teachers know how this sounds to some people. Still, they do not waste much time on philosophical debates about the pros and cons of assimilation. They have no desire to take anything away from these children's cultural heritage. But the children are in America now, and they must learn English. That is why the preschool was founded. It is why so many Southeast Asian parents send their sons and daughters to these classrooms. The teachers begin at the only place possible, which is at the beginning. With the smallest and simplest of lessons. They show the children how to answer when their names are called. They read them Goodnight Moon. They lead them in silly songs about animals in funny clothes; they lead them in games of Simon Says. They teach them the words for the color of the sky, the color of the leaves and the color of a stop sign. Every morning they ask them what they had for breakfast because they want to get them talking and because the want to know if the children are getting enough to eat. They talk about how smart the children are to already know another language, the language they and their parents speak at home. But while they are here at school, the teachers insist that the children converse only in English. The teachers show the children how to flush the toilet and wash their hands. They lecture them on the importance of sharing. The teach them not to hit, kick, scratch or bite one another. When assaults occur, as they inevitably do with small children, they teach them how to say they are sorry and mean it. The children are not the only ones who are learning. As the weeks pass, the teachers are sorting out the challenges before them. They are studying their new students, getting to know their quirks and temperaments. As Mrs. Chip puts it, they are watching the children unfold. 5. Inside the house that Mrs. Chip drives by—the same house where Mari's family moved immediately after the death of Soi Lieu—life has gone on. Linh Truong reports that his family is doing better. He works hard—six days a week, twelve hours a day—at an Asian market. He has remarried and says that he could not have made it through without his second wife, Thach Phen, who has helped raise Mari and her five older brothers. He is also deeply grateful to Mari's preschool teachers and Mrs. Petrie. They gave from their hearts, he says. Mari is 8 now, and growing tall. But her eyes look the same—fierce, startling, beautiful. She is in the third grade at Woodlawn elementary. She is frequently on the honor roll, and a wall inside her family's living room is papered with certificates of her academic achievement. "My dad says he wants me to be a doctor," says Mari. "Then he changed his mind. He wants me to be a weather reporter." "What do you want to be?" I ask. "I want to be a doctor or a nurse." Mari clearly has the intelligence to do whatever she wishes. By now she speaks four languages—Cambodian, Vietnamese, Thai and English—and is currently learning Chinese. Every weekend she takes classes in Cambodian culture and has learned to perform traditional dances. Her dance partner is the same boy her mother hoped Mari would one day take as a husband. Mari only smiles when she is asked about the boy and the possibility of their sharing a future together. Mari's father respects his deceased wife's hopes but also understands that it will be up to Mari to decide what she does with her life. Mari does remember Mrs. Crow, Mrs. Chip and Mrs. St. Clair. She can still recount the day Mrs. St. Clair took her home and gave her a bath and some lunch. She remembers playing with the Barbies that morning, remembers the peanut butter and jelly sandwich that Mrs. St. Clair made for her. She even recalls the smell of the fresh-baked bread. There is someone else that Mari recalls, and that is her mother. She talks about Soi Lieu; she writes about her in her journal at school. When her mother's name is mentioned in front of her, Mari beams. On the night before Thanksgiving, I met with Mari and her father at their home. Mr. Truong's English is limited, but with the help of an interpreter, he told me that sometimes he looks at his only daughter and wonders who endowed her with such grace and strength. He knows it had to come from either himself or Mari's mother, or both. And if it came form them, he said, then it must have come from their parents, and their parents before them, and theirs before. He looks back through the generations of their families, he said, and he sees the best of them all, carried forth and living today inside his daughter. As we spoke, Mr. Truong sat very still in a chair in his living room. It was dark outside. Through the open windows we could hear a fresh rain falling through the trees outside the house. Mr. Truong said he is happy that Mari has such respect for her mother's memory. He explained that, to this day, she believes that Soi Lieu lives in the sky and watches over them from heaven. And when it rains, he said, Mari still insists that Soi Lieu has made it happen. Mari, he said, believes her mother sends the rain as a blessing. For her daughter. For us all. About This Story

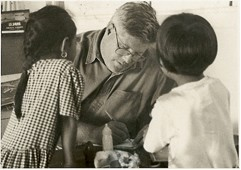

Cherie Diez, St. Petersburg Times Thomas French comments about his series "The Girl Whose Mother Lives in the Sky": Several years ago, I learned about the Southeast Asian Preschool while taking my own children to their preschool, Lad ‘n Lass, which shares the same grounds at a St. Petersburg church. In the mornings, I would hear the Asian children singing in their classrooms or would see them playing outside. I wondered who they were and how they came to America. I wondered, too, about their parents and what their experiences meant for their young sons and daughters. In the spring of 1994, I set out to find the answers. Along with photographer Cherie Diez, I began hanging out with the students and their teachers. We embarked on the story with the permission of the preschool and United Methodist Cooperative Ministries, which oversees the school. When we found children we wanted to describe by name and detail, including Mari Truong, we also obtained permission from their parents. Some of the children at the school go by two names, a formal Asian name and a nickname, which is sometimes American. Since this story centers on the children's experiences at the preschool, we refer to them by the names used there. I spent nearly eighteen months at the school. In the years following, as the boys and girls headed for elementary school, Diez and I kept track of some of them. "The Girl Whose Mother Lives in the Sky" is an account of what we saw at the preschool and of what happened to those children. One final note: This story chronicles a period in life—the time just before children formally enter the world—rarely covered in a newspaper. This period, when the children are shaped and molded in the most elemental ways, is crucial to their future. But the events described here seem quiet, small, almost episodic. Furthermore, because the children were so young at the time, they now remember almost none of it. They have forgotten the games they used to play, the songs they used to sing. No matter. This is still their story. The lost story, retrieved from days before memory, of how they took the first steps toward becoming themselves. |