A Civil Action: fighting got enviormental justice in Woburn

Nashua River

International Accord to Clean up the Rhine River

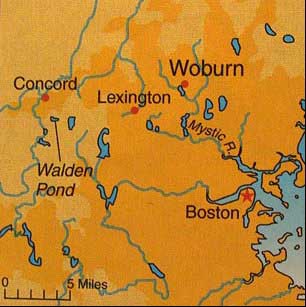

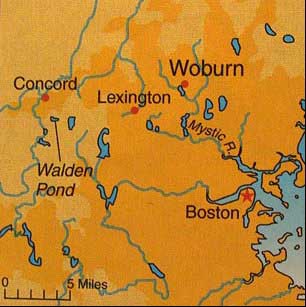

A Civil Action Woburn, Massachusetts is a small, industrial city on the outskirts of Boston.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Woburn was a major leather

manufacturing center with as many as 20 tanneries in operation at one time.

Between 1853 and 1929, the Woburn Chemical Works was one of the largest industrial

complexes in America. Centuries of careless toxic waste disposal badly contaminated

the soil and groundwater under much of the city, and for many years residents

complained that their well water tasted and looked terrible. In 1958, when the

city drilled two new wells (designated G and H) to serve the growing population,

the city engineer warned that the water was contaminated but the wells were

used anyway for domestic consumption. In 1971, young Jimmy Anderson, who lived in the part of Woburn served by

these wells was diagnosed with leukemia. In talking with neighbors, Jimmy's

mother, Anne, discovered that 11 other children within a few blocks of her house

also had cancer. Depending on how you calculate the sample size, this was between

2.5 and 12 times the expected rate of childhood cancers. Was this merely a statistical

anomaly or an ominous pattern? What might be causing these tragic illnesses?

Could it be something in the water?  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image17::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22974/Image17.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image17 (22.0K)</a>Image17 <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::Image17::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22974/Image17.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Image17 (22.0K)</a>Image17

Although their suspicions were initially dismissed as emotional and unscientific,

Woburn residents finally learned in 1979 that the water from wells G and H was

indeed contaminated with a variety of metals and organic solvents including

several suspected carcinogens. Coming just a year after a similar revelation

about chemical contamination and links to childhood diseases at Love Canal in

Niagara, NY, this discovery encouraged Anne Anderson and others to begin to

ask who was responsible for polluting their neighborhood. In 1982, just a year

after Jimmy died, Anne Anderson and seven other families whose children also

had cancer sued the W. R. Grace Company and Beatrice Foods for damages caused

by negligent disposal of toxic wastes on their properties near the wells. The

families were represented by attorney Jan Schlichtmann of the public-interest

law firm, Trial Lawyers for Public Justice of Boston. Both Grace and Beatrice immediately filed motions for dismissal, claiming

that even if they had dumped toxic wastes, the plaintiffs couldn't prove which

of the many pollution sources in Woburn was cause of a specific disease in a

particular person. These two corporations were chosen as targets out of all

the possible industries in Woburn, their lawyers argued, simply because of their

deep pockets. The judge ruled, however, that the case had sufficient merit to

proceed to a jury trial. After four years of interrogatories, deposition of

hundreds of witnesses, thousands of pages of documents, extensive examination

of medical histories and physical conditions of each of the plaintiff families,

and investigation of the industrial sites, the case finally went to trial in

1986. In the discovery process, the plaintiffs conducted their own on-site investigation

that revealed drums of toxic chemicals buried on the Grace property. Conviction

on charges that the company had lied to the EPA about when and where wastes

had been disposed didn't help the defense in the civil trial. After a five-month trial and seven days of jury deliberation, the case

against Beatrice was dismissed, but the jury found that Grace had negligently

contaminated the Woburn wells. The jury could not decide, however, when contaminants

from the Grace property might have reached the wells. Was it before or after

the children developed cancer? This uncertainty led the judge to dismiss the

verdict and order a new trial. Rather than go through the process all over again,

both sides agreed to settle for $8 million. Grace also agreed to participate

in a $68 million cleanup of the wells, the most expensive Superfund project

in Massachusetts at the time. Because the case was settled out of court, it doesn't create a legal precedent,

but it was one of the first times that plaintiffs succeeded in gaining compensation

in an environmental injury lawsuit. As a story of a few local families challenging

corporate giants, it gained national attention, and served as a warning to corporations

that they can be held liable for personal injuries from negligent disposal of

toxic wastes. A 1995 novel by Jonathan Harr about this case, titled A Civil

Action, was turned into a movie by the same name starring John Travolta and

Robert Duvall. Check out the novel or movie if you'd like to see more about

how the drama unfolded. This case illustrates both changing attitudes in the United States towards

waste disposal and environmental liability as well as use of the courts to redress

personal environmental injuries. In this chapter, we'll examine both how environmental

policy is formed as well as how the legislative, legal, and administrative systems

work to accomplish policy goals. Cleaning up the Nashua River The Nashua River meanders for about 90 km (55 mi) through a heavily industrialized

region in central Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire before joining the

Merrimack River near the town of Nashua, New Hampshire. For years the river

was so badly polluted by paper mill effluents, printing inks, municipal wastes,

and agricultural runoff that it was virtually an open sewer. It ran a different

color every day, depending on what was being dumped into it. Great globs of

toxic yellow-orange sludge often covered the surface. Foul smells drifted through

nearby communities and dead fish floated gently down the stream. In 1962, Marion Stoddard moved to Groton, Massachusetts, not far from the

Nashua River. Disgusted by the water's condition, she decided to organize her

neighbors to begin cleaning it up. The first step was to identify who cared

about the river and how they might pool their efforts. A Nashua River Clean-up

Committee was formed (and later reorganized into the Nashua Watershed Management

Association to include land-use issues). Next, local, state, regional, and federal

agencies were contacted to find out about plans for the river and to identify

relevant statutes and regulations. An important weapon in this campaign was provided by the Massachusetts

Clean Water Act, which provided for public hearings at which citizens could

comment on water-quality standards. With a little community organizing and publicity,

hundreds of citizens were mobilized to attend hearings and voice their demands

for clean water. A reclassification of the river resulted in new stringent standards

for pollution control and wastewater treatment. Local industries complained,

but most of the costs were paid by federal grants. Another key to success was the ability to get widely different people to

work together. The general manage of one paper mill was persuaded to serve on

the Nashua Watershed Association board of directors together with zealous environmentalists

and conservative farmers. A broad-based coalition of private citizens, labor

unions, business leaders, and politicians was persuaded that having clean water

made good economic sense. In an unheard-of partnership, the Army, local communities,

and two state governments worked together to sponsor clean-up days in which

tons of trash and garbage were dragged from the river. The end result was spectacularly successful. Six new wastewater treatment

plants were built. A 2,400 ha (6,000 acre) greenway lines the riverbank to protect

the watershed and provide for public recreation. The river now runs clean and

clear; people once again use it for swimming, fishing, and boating. Property

values have risen and new companies have been attracted by high environmental

quality and community spirit. The river that had been given up for dead is once

again alive and well. The EPA recognized Marion Stoddard and the Nashua Watershed

Management Association for their environmental leadership. It didn't take great

technical knowledge or wealth to do what they did; jut a concern for nature,

perseverance, savvy use of the media, some organizing skills, and a willingness

to work together for the common good. You could do the same. International Accord to clean up the Rhine River April, 1999

Basel, Switzerland

The Rhine River, which flows through some of Europe's biggest industrial

districts, has long suffered from severe pollution, including chemical

spills that have caused catastrophic fish kills. At times the water has

been so contaminated that long stretches the river were emptied of living

fish. In recent years several European governments have made special efforts

to clean up and protect the Rhine. On April 12 conservation efforts moved

forward with a new international convention (agreement) on the protection

of the Rhine. Five countries signed the convention: Switzerland, France,

Germany, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands (see map).

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::Rhine::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22974/rhine.gif','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Rhine (42.0K)</a>Rhine <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::Rhine::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22974/rhine.gif','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Rhine (42.0K)</a>Rhine |

The new agreement has impressive environmental protection goals. Included

among these goals are

- Habitat protection along the river's banks.

- Flood management, including aims to re-establish parts of the river's

natural course. By allowing the river more room to flood, severe floods,

such as those that took place in Germany and the Netherlands last fall,

could be avoided.

- Reintroduction of salmon, after an absence of almost 50 years, as

far upstream as Basle, Switzerland. Recent pollution prevention efforts,

as well as the installation of fish ladders to help the fish get around

dams, have already helped salmon return to lower stretches of the river.

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::Rhincast::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22974/rhincast.gif','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Rhincast (10.0K)</a>Rhincast <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=gif::Rhincast::/sites/dl/free/0072452706/22974/rhincast.gif','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif">Rhincast (10.0K)</a>Rhincast |

The new convention also gives some environmental groups the right to observe

progress by signing countries. Giving these groups a voice is an important

step in ensuring that the words on paper will be translated into some sort

of actual progress. Also important in the effectiveness of the agreement

are extended powers of oversight and enforcement that will allow an international

commission to ensure that signatory countries live up to their promises. For further information, see these related sites: European Rivers Network

homepage Description of the

Rhine River, from the World Meteorological Organization To read more, see Environmental Science, a Global Concern, Cunningham and Saigo, 5th ed.

Water pollution: p. 435-37

Types of water pollution: p. 437-443

Water pollution control: p. 451-455

Environmental Science, Enger and Smith, 6th ed.

Wastewater treatment: p. 302-304

Water use and pollution in industrialized and developing countries: p.

300 |

2002 McGraw-Hill Higher Education

2002 McGraw-Hill Higher Education