(See related pages)

by Eric Newhouse

Liquor is a common commodity in Montana. Most people drink in moderation. Friends share a story over beer and a bartender pockets tips that help pay for his college textbooks. Some Montanans abstain. Others are addicted. Those who abuse alcohol often pay the price with their health, their finances, their families, their social lives and their jobs. The flow of alcohol can be traced as it courses through everyday life on any given day. Following is a diary of that Friday in Great Falls. 5:30 a.m. It's wakeup time at the Great Falls Rescue Mission, which has been called the final pit stop before the graveyard for those unable to handle their addictions. "This is the last stop for most of these folks," says Glenn McCaffrey, director of the Rescue Mission. "They're almost literally one yard from hell." He says about half abuse alcohol, half abuse drugs. This morning, the Mission houses seven regulars working off their room and board and five other transients. "Most of these people get government checks of some sort, and when those checks run out later in the month, we begin to see them in greater numbers," says McCaffrey. Breakfast is at 6 a.m. Today it's grits and eggs, and clients are expected to help clean the cafeteria and sweep the dayroom before they head out. "A few are actually looking for jobs," says McCaffrey, "but most of the professionals will be out collecting cans to get the money for alcohol or drugs. "But we have a rule here—if you come in intoxicated, you forfeit your bed." 8 a.m. By county ordinance, there can be no sale of alcohol between 2 a.m. and 8 a.m., so that's the earliest the bars can open. The old Maverick Bar in downtown Great Falls used to start its happy hour at 8 a.m. for the night shift workers and could be a rowdy place in the early morning hours. Some bars still open at this hour, including the Lobby Bar, the Prospector casinos and the Half Time Sports Bar. 8:15 a.m. Tom Jerome, a former ranch hand from Miles City, is sitting on a bench in the Rescue Mission, already drunk and waiting for coffee at 9 a.m. Considering the Mission's rules, how did he spend the night there? "I didn't," he says. "I usually spend the nights out." But the gray-tiled dayroom can be a dry place, so Jerome periodically slips out into the alley where he has a cache of beer waiting for him. "I pick up cans," he says. "If I go all day, I usually can get around 30 pounds." That's $7.50, and Jerome says he spends most of it on drinking beer with his friends. "Tom is what I call a suicidal drinker," says McCaffrey. "He just drinks himself to death every day. I've watched him deteriorate over the past few years." That's an unfortunate reality at the Mission, where success stories are rare and people are hitting bottom at a younger age. "One thing that really worries me is that we're beginning to see a lot of 18- to 25-year-olds here now," says McCaffrey. 8:30 a.m. Officer Mark Thatcher of the Police Department's DARE squad is standing before Mrs. Figarelle's class at Blessed Trinity Catholic School, preparing to talk about the evils of alcohol, drugs and gangs. But first, he opens a box of questions from the 19 fifth graders: Do you ever arrest anyone who doesn't want to be arrested? Most people don't want to be arrested, responds Thatcher, remembering in particular a 16-year-old drunk who wanted to avoid being charged with minor in possession. "I put him up against the car to frisk him, but he took off and ran from me," he remembers. "I chased him and tackled him, but during the scuffle, he bit me on the inside of the leg. "Another officer joined me at the scene and we subdued him and threw him in the back of a police car," says the officer. "Then he spit in my face and kicked out the rear window of my police car." Do many people abuse drugs and alcohol? "I know quite a few people who take drugs and a lot of people who drink too much," says Thatcher. How about police officers? "I don't know of anyone who takes drugs, but I do know of a few people who drink a little too much," he responds. "I don't think they're alcoholics, but they may let the stress of their jobs get to them a little too much." 9 a.m. The workday has started in Great Falls. All told, about 35,000 people hold jobs in and around the city. Some, suffering from hangovers or other alcohol-related problems, won't make it to work today. Statistics say fewer than one American in 10 has a drinking problem, and two-thirds of them hold jobs. Employees dependent on substances like alcohol have two to three times the normal absenteeism rate, according to VRI, a company that contracts with businesses to provide counselors and programs to troubled employees. 9:15 a.m. The Cascade County Tavern Association board of directors was to meet at the office of its executive director, John Hayes, on North Star Boulevard, but none of the board members showed. Hayes has prepared a report, however, reporting that the association's major fund-raiser the week before had raised $12,000, most of which would go to support local charitable activities. "We average 10 to 12 calls a week for donations," says Hayes. "Our board meets once a month to send checks to those we feel we should help. "Our emphasis is on kids," he says. "For example, we usually help the St. Vincent DePaul Society with their annual outing that takes about 40 kids up to a camp near Monarch. "That costs $1,500 to $2,000 each year and we finance most of it," he adds. "They make the kids pay a buck apiece, and we make up the difference." On this Friday, the tavern association received two requests for charitable donations, and it wrote checks for $250 to St. Vincent's and $400 to the food bank. 9:30 a.m.

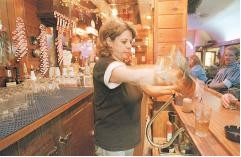

Fatz is one of about 3,000 people employed by bars and restaurants in Great Falls. The annual payroll for these jobs? About $9 million. 11 p.m. Police dispatchers begin receiving calls that vandals have spray painted homes, cars and property in a four block area on the West Side. More than 30 people are victimized by the vandalism. When an 18-year old man is later arrested, he tells police he was intoxicated when he went on the spray painting spree. 11:10 p.m. Officer Stimac is still mulling the parting words of a Benefis emergency room technician, who had been complaining about the lack of a drunk tank in the city. As a result, the technician said many drunks who can't be discharged are left occupying hospital beds until they sober up enough to allow them to be released safely. "A lot of the bigger cities have drunk tanks," says Stimac, turning his squad car off Fox Farm Road onto 10th Avenue South, "but does that condone a drunk's actions? "There's no incentive to stay sober if you know you've got a warm place to stay for the night and maybe even breakfast if you sleep it off. "But it is a problem," Stimac adds. "What are we supposed to do with a drunk who really just needs to sleep it off?" 11:15 p.m. There's a call to a teen-age drinking party in Prospect Heights. Three officers arrive with their lights off and park their squad cars around the corner from the party. 11:45 p.m. Four intoxicated males are reported fighting in an alley on the lower South Side, but they have left the scene by the time three squad cars get there. 11:55 p.m. It's another call for a fork-stabbing at 504 4 1/2 Ave., S.W. Officer Stimac can't believe it, but he's rolling fast with lights flashing and siren sounding. There's an ambulance and EMT personnel in a fire truck right behind the squad car. When he hits the scene, though, it's a different problem: two women brawling in the doorway of the house he had left just a couple hours earlier. "She got mouthy with me, and I punched her," says one of the combatants. The other woman asks an officer if he'll give her a lift to Cindy's Bar, just around the corner. Midnight Officer Stimac checks in briefly at the police station. In the first six hours of his shift, he has handled eight calls. All but one involved alcohol in some way. "That's about the average I had anticipated," he says. "But the probability of alcohol-related calls increases as we get closer to closing time." 12:15 a.m. Joe's Place on 9th Street across from Holiday Village Mall is tame by comparison. Several dozen people are drinking, chatting, gambling, but no one is out of control. "It's been fairly quiet in here tonight," says bartender Tom Knutson. 12:30 a.m. Just down the street a block, it's livelier at the Other Place. The music is a little louder and the crowd a little bigger. One patron with a point-and-shoot camera wanders through the bar, capturing the action. "Hey, cut that out," snaps a guy in a baseball cap who has been hugging a woman by the bar. "Man, you're going to get us both killed." 1:30 a.m. The J-Bar-T is packed, and Alibi, a Billings band, is playing some old favorites. The dance floor is full. One blonde is relatively formal in a low-cut, black velvet dress with a heavy silver necklace and high heels. Another is fashionably informal with her red vest unbuttoned to show her lacy black brassiere and the elaborate tattoos on her chest and shoulders. Hot off the dance floor, a young man in a white cowboy hat stands beside a woman perched on a barstool. She glances around, then begins unbuttoning his denim shirt and nuzzling his chest. Embarrassed, he flushes and backs away. Beside them, a middle-aged man is asleep, the brim of his black cowboy hat just resting on the bar. Beside his head is his beer bottle. "We're going to let him sleep until we close," says the barmaid, Laurene Lawson. "Then we'll escort him out of here, make sure he's OK and get him a cab if he needs one." With that, the band winds it up for the evening and the lights come on. "There's a point where you have to exercise self-control," says Page Lutes of Bozeman, looking down at the sleeper. "When you can't maintain control, you've lost it. And it takes a lot of control sometimes to maintain it." Off the dance floor comes a younger couple. They begin to arouse the sleeper. Finally, they get him to his feet and begin to lead him out of the bar. About halfway to the door, however, he lurches into a young woman and pinches her butt. Without hesitation, she whirls him around, crouches down, and bites the label off the rear pocket of his jeans. Laughing she stands with the label between her teeth. Outside the bar, the sleeping drinker comes to life in the chilly night air. He's Knute from Jordan, he announces. As the parking lot is beginning to clear, Knute is asked if he is going to be driving home. "It's too far to drive home tonight," says the young lady who has been helping Knute out of the J-Bar-T. "So we'll take him to a motel tonight." "And tomorrow," she adds, "we'll probably start all over again." Newhouse profiles three alcoholics who, he writes, are battling lifelong addiction: Alcohol has turned Broderson's life into a real-life nightmare. He's not alone. More than 120,000 Montanans—about 15 percent of adult residents—range from problem drinkers to full-blown alcoholics, according to the state health department. Some have managed to quit drinking, but about 75,000 remain in need of treatment, state health officials say. Many are closet drunks, who seem to function normally, as did Anne, who led a double life in Great Falls for years. The American Medical Association defines alcoholism as a chronic, progressive, apparently genetic disease. Untreated, it brings denial, fear, even death. Alcoholics aren't the only ones affected. It's estimated that one alcoholic has a direct impact on the lives of at least four family members, friends and co-workers. Tammera Nauts knows that cycle well. She's the addiction specialist for the Great Falls School District, and an alcoholic who lost her husband and nearly lost her daughter over her drinking. Here are Bill, Anne and Tammera's stories. Bill's Story

His treatments at the Montana Chemical Dependency Center in Butte run $3,000 to $4,000 a visit. Most of that is aid from a state alcohol tax. At 14, Broderson started drinking. He dropped out of school and spent as much time as he could on the golf course, a 12-pack tucked away in his cart. "There was always alcohol in his home," said state Rep. Hal Harper, D-Helena, Broderson's best friend in junior high. "I think he just got sucked down the tube." In his 20s, Broderson was having blackouts. "I woke up in Idaho once and had no idea how in hell how I got there," he said. Through the years he has tried many times to quit drinking, he said. Sober for a year once, he had been admitted to MSU-Northern's School of Nursing, had been given a grant to cover his tuition and had worked a deal to paint rooms in exchange for food and lodging. Then a friend invited him out and bought him a soft drink but drank a beer in front of him. "I thought if he could have a beer I could have one, too," he said. "But after one beer, I wanted another. In the course of a week I had sold my Volvo, my fishing gear and most of my possessions." He has since been living in downtown Great Falls, subsisting on food stamps and odd jobs. A few weeks ago, he tried to commit suicide. "I just gave up," he said. "I'm not contributing anything. I'm just taking up space." Even as he sat in the hospital, Broderson was craving whiskey. "I need a shot," he said softly. "There's a guy on my shoulder who keeps saying 'No,' but the other guy in red on my other shoulder, he has a louder voice or something." It's tragic, Harper says. "If he could have gone down a different road, who knows what he could have done," Harper said of his childhood friend. "He was smart, popular with the girls because he was so cute. He could have done pretty much anything he put his mind to. "But now, it's just amazing he's still alive." Anne's Story Anne, a Great Falls grandmother, is a less visible alcoholic. She was outgoing and efficient, unflappable in her handling of the public, the phones and her balky computer before she retired. She drank only in social situations—and at home. Now a member of Alcoholics Anonymous, Anne asked that her name not be used. She, too, has a family history of alcoholism and a difficult childhood. Unlike Broderson, who is physically addicted to alcohol, Anne has been diagnosed as a psychological alcoholic, who instead uses the drug to cover emotional pain. An only child with an alcoholic father who ignored her and a mother who smothered her with attention, Anne, "never felt like I fit in." Drinking helped her feel like she belonged, but that feeling always dried up the next morning when she dried out. "A lot of alcoholics drink because they're lonely," Anne said. "I call it the 'hole in the soul' disease, because there's a void in your life that you're always trying to fill." Anne said she spent her life trying to please others but ignoring her own needs. "Neither my husband nor I ever knew who I was because I was changing so fast trying to become what I thought my husband wanted." After three suicide attempts came a divorce. After two DUI tickets came a recovery program. But even a psychological addiction is hard to kick. "I spent a lot of my early recovery in pain," she said. "I'd want a drink so bad. I'd look at the clock and say, 'God, let me stay sober for the next five minutes.' A lot of days, I got through five minutes at a time." It was also important for her to examine the psychological roots of her illness. "I spent a lot of time trying to peel away my excuses and my defenses," Anne said. "But when I finally got to the bottom, 98 percent of the time I realized that I was driven by fear that I was inadequate." Tammera's Story Tammera Nauts began drinking in her early teens, when her family would party with friends after racing sailboats. She would sneak a beer or pour some liquor in a pop can. "I always felt like I was a little different," she said. "I never fit in. But when I drank, it filled a void and made me feel like I was part of the crowd." Her first big drunk came when she was 14: "I drank eight shots of whiskey in half an hour, blacked out and was raped. "I didn't tell anyone," she said, wiping a tear from her eye. "There was the additional shame of having put myself in that position. I felt I was partly responsible for the rape." In her later teens, she added marijuana and amphetamines to her binges before she turned her life around the first time. "At 18, I got into Transcendental Meditation, became vegetarian, didn't drink or smoke, didn't even use sugar," she said. "It was the epitome of a lifestyle I wish I could get back today." Three years later, she got a job in a restaurant with a great wine cellar. She began drinking again, and became a heavy cocaine user. She married at 20, became a mother at 21, went back to school and got a divorce. "I knew there was something wrong—I was spiritually bankrupt, my body was breaking down, and none of my relationships were working out—but I never attributed it to alcohol," she said. Then the alcoholic mother of an alcoholic friend killed herself. That killed Nauts' denial. "That was the first thing that really opened my eyes to the power of alcoholism," she said. Discovery was painful. "I began to realize that alcohol held my family together," Nauts said. "Our connection to each other was that we drank together." Clean for 12 years, she is now a certified chemical dependency counselor, helping others avoid the problems she has experienced. Nauts considers herself lucky to have survived alcoholism, but she has paid a price. "I lost my husband and almost lost my daughter," she said. Nauts says conquering her illness has been good for her. "Knowing that I could survive something so devastating and that I chose life makes me feel like I can do anything I set my mind to and that I can create any kind of a life I want to," she said. "It's very empowering, although I know there's a higher power who is lovingly supporting me," Nauts added. "I couldn't do this on my own—I'm just not that powerful." Newhouse tells how he reported and wrote the story: Divorces, lost jobs, battered wives and children, crime, drunken drivers, medical costs and car wrecks are the raw materials for newspapers. They show up in some part of every newspaper every day. Newspaper reporters and editors have become so accustomed to these social problems that we rarely wonder why they are there—or if they are necessary. The Background Several years ago, the Great Falls Tribune did a series of stories on the unsolved murders on one Montana Indian reservation. All were alcohol-related, and most were unsolvable because all the witnesses were too inebriated to cooperate. Those stories stuck in the mind of Tribune Executive Editor Jim Strauss. I, in turn, had been watching the national tobacco settlement unfold in the late '90s and had been impressed with the way the lawyers had tied together the social and economic ramifications of smoking. Why hadn't the newspapers provided that perspective? I wondered. Then I realized we had a perfect opportunity to do the same thing with alcoholism. So I came before a meeting of Tribune editors in the early fall of 1998 with a conventional proposal, four or five major stories on alcoholism that would run over the course of a week. But no one could agree on what those four or five stories should be—there seemed to be a lot of important things that were falling by the wayside. With no decision, I came away disappointed that no one seemed to like the idea. A Year's Series A couple of weeks later, Strauss surprised me by asking whether we could tackle the whole issue in a 12-part series, one part a month for a year. I was elated and told him yes, absolutely. By the end of that afternoon, I had an outline sketched out. We fine-tuned it a little, but it essentially stood for the next year. Vision and planning were one key to the success of this project. I did much of the statistical research for these stories two or three months in advance. Then, knowing the facts, I would begin to look for real-live people to illustrate the trends. Another key was our community. Great Falls isn't much different than any other city in America, but it's still small enough that you can put both hands around a local problem, lift it up and look at it from several angles. Trust in Newspaper And the Tribune is the state's newspaper, still trusted in the hearts and homes of its loyal Montana readership. That was critical to a project in which we would ask alcoholics to share some of their darkest secrets with our readers. To make their stories believable, we knew we would have to quote people by name—and use their photos on the front page of our newspaper. To those people, who had the courage to trust us with their stories, I owe an immense debt of gratitude. Just think of how you would feel if someone like me came up and began asking the most personal of questions about behavior you had been accustomed to hiding. I'm also awed that the Tribune, with a circulation of about 40,000, had the courage to make such a huge commitment to a project. I figure I spent half of my work year in 1999 writing this series. I also had a photo editor, Larry Beckner, assigned to work with me. We put a serious strain on the editors, copy-editors and graphic designers, and we ate up a massive amount of news space. Even worse, the project grew in size as it went along. We had envisioned a one-day package each month, but the segments began growing into two- or three-day packages because there was so much material. AA Meeting Early on, I faced one problem that could have scuttled the whole project—and I handled it without knowing the severity of the wrong decision. I was invited to an AA meeting, was introduced by name but thought that I needed to tell the folks sitting around the table that I was a newspaper reporter working on a series of stories and that I was there to learn. No one seemed to object—until I left the room after the meeting and ran into a delegation of women who wanted me to leave my notebook in the meeting room. Why? They explained there was an AA tradition that what was said in the room stayed in the room. We discussed that problem. Finally, I said that if I agreed to their request, it would waste several hours of my time; how would they propose to make that up to me? I asked. Surprised, they retreated, huddled and returned to tell me they would join me outside on a park bench and tell me their stories in a way that wouldn't cause pain to those around them. Well, that began to make sense to me, so I agreed. Doing What's Right Several weeks later, I was talking with a family about doing a profile of an alcoholic family, when the wife brought up the meeting incident. She asked if I intended to use the material from the meeting room, and I said I would not. That's good, she said, because the alcoholics in this town are a tight-knit community, and if you had violated our tradition, not a one of us would have talked to you. That taught me a lesson. It would have been very easy to stand on a principle, but I would have lost much more than I gained. I learned that sometimes you have to trust your instincts and simply do what you know to be right. As long as I'm confessing, I should tell you I violated a second principle of journalism. I was interviewing a fetal alcohol syndrome counselor on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, and it was a very disturbing interview. She drank heavily during her pregnancy and told me that when she delivered her son that a nurse put him on her breast; she could smell the alcohol on his breath and knew that he had been born drunk. She then described what her drinking had done to him, physically, intellectually and emotionally. She cried a lot during the interview and I did too, although I tried to keep my tears inside. As I was leaving, she became worried about how all of this would look in print and asked if she could see a copy of the story in advance. My first reaction was a big red flag. The second was that she had entrusted her life to me and that I had an obligation to let her know that it would be treated honestly, fairly and sensitively. So I agreed and sent her a rough copy of what I proposed to use from our interview—nothing of the rest of the story—with a note that said I couldn't guarantee that the story would run in exactly this form or exactly this language, but that I planned to add nothing new to what she would read there. I had feared that she might back away from some of the most damaging statements, but that didn't happen. I finally came to understand that she was as interested in telling her story as strongly as I was. But what did happen was that she straightened out small details, dates, relationships. It turned into an excellent quality-control strategy, and I used the same approach with four or five other of the most sensitive interviews in the series. Sources Volunteered The major writing challenge was getting alcoholics to talk with me, on the record, using pictures. Early in the series, I used to wake up in the middle of the night and wonder how I would ever find anyone to talk with me about next month's topic. But as the series progressed, people began calling and volunteering their help. Sometimes this series reminded me of mountain climbing. Great Falls is right on the edge of the Rocky Mountain Front, and I've climbed a lot of mountains in the dozen years I have lived here. It seemed to me that what I was doing was taking a month to ascend a 10,000 foot peak, standing for a day enjoying the view, then descending, wading through the inevitable creek, and starting up the next mountain. Worse, there were peaks ahead for as far as I could see that year. |