(See related pages)

by Elizabeth Leland The Charlotte Observer Gene Cheek was 12 when a judge took him from his mother. It was a Monday morning, Nov. 18, 1963, and Gene remembers being excited because he didn't have to go to school. He put on his best clothes—a white shirt and his Sunday coat, a size too small—and rode with his mother on a city bus to the courthouse in downtown Winston-Salem. They were going to get the $413 in child support his father owed them. They'd go shopping afterward. His mother sat up front in the courtroom to the right of the judge. His father and an uncle sat to the left. Gene remembers goofing off by himself on a bench a few rows back, not paying attention to what anyone was saying, when he heard his mother crying. He walked up front. The gray-haired judge in the black robe was telling her something, and as Gene listened he realized it was not about money. It was about her boyfriend. The judges said it wasn't good for Gene to live with her because she was seeing a Negro man and had a Negro baby. Gene's mother pleaded. "I'm a good mother," she said, her voice breaking, tears wetting her cheeks. The judge gave her a choice: Give up the baby or give up the boy. Gene was still a child, but since his father left, he fancied himself the man of the family. He remembers whispering in his mother's ear, telling her that if the judge sent Randy away, they'd never see him again. Randy was too little to find his way back home. Gene was older. He could get back. They can take me, he said. The judge ordered Gene into the custody of the child welfare department. Two bailiffs grabbed him by his arms. Gene cursed and kicked and tried to break loose. His mother cursed and tried to take him from them. As the bailiffs dragged Gene from the courtroom, he shouted at his father and uncle: I'll kill both of you for this! They locked Gene in a room at the juvenile detention center. A short time later, he heard someone banging on the front door, then his mother's voice, hysterical. They sent her away. They sent Gene away. It wasn't until 37 years later, just this February, that Gene Cheek discovered a document confirming in writing what he remembered of that day when he was 12: He was taken from his mother because she had "been carrying on a continued relationship with a Negro man by whom she has had a child." No other reason. A white woman with a black man. Gene had to find out more. It wouldn't happen today, and he needed to understand how it could have happened in 1963.

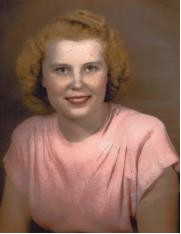

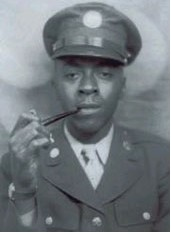

Sally and Jesse in Love There was a time when Gene's parents were new to love, when his father cradled his mother in his arms, when she smiled if he walked into the room. They made a good-looking couple, Jesse and Sally Cheek. She had a clear, pale complexion that her girlfriends envied, blue eyes, sandy blond hair. He had green eyes and slicked-back brown hair. Gene was born during their second year of marriage, on March 2, 1951, at City Memorial Hospital in Winston-Salem. Sally was 20. Jesse, 24. They named their baby Jesse Eugene—Jesse after his father, Eugene after a brother of Sally's who died before she was born. Sally kept track of his firsts: The first time he ate cereal, 6 weeks old. His first tooth, 6 1/2 months. His first words, 15 months. Gene loved the way his mother's alto voice seemed to lift the ceiling when she belted out tunes by Dean Martin and Nat King Cole. She was a mill hand. She sewed slips and nightgowns and other lingerie on the line at Indera Mills. His father worked on-again, off-again, a few years as a meter reader for the city, another time on a dairy farm. They didn't have much in the way of furniture or clothes, but Sally never let on that their life might be hard. Most everybody they knew lived the same way. Sally would sit straight-legged on the linoleum floor, lean the bed and play Parcheesi with Gene for a whole morning. Just one more game, he would beg and Sally obliged. Gene was as playful with children as Sally was. He inherited her nurturing spirit, her blond hair. He had Jesse's green eyes and could be as hard-headed as both of them. Gene got into mischief at a Cheek family gathering one time, and Jesse demanded a whipping. Sally took Gene into a bedroom, shut the door and told him to yell when she hit the bed. The only times Gene remembers getting angry with her was when he'd say something, and she'd scold back: That sounds just like something your dad would say. Gene didn't like to be compared to his father. When he wasn't drinking, his family says, Jesse Cheek could kind. The problem was, it was a rare day when Jesse didn't drink. He'd buy a couple of cases of Budweiser and drink himself into an ugly mood. He'd stumble through the front door, drunk and ornery. Gene recalls the fights: "What are you looking at?" Jesse would shout at Gene. "You leave him alone, you drunken son of a b----," Sally would say. That made Jesse angrier and he'd take it out on Sally. He called her names. Sometimes he slapped her. Jesse Confronts Sally On Easter Monday, April 3, 1961, someone called Jesse's brother, Bobby, and said Jesse's car was parked at a house in colored town. Bobby says he told Jesse, and Jesse asked him to take him there. Jesse knocked on the door of the house on 9 1/2 Street. Sally opened it. Jesse and Sally yelled so loudly at each other, Bobby says he could hear them from the street where he was waiting in his car. Jesse demanded to know what Sally was doing there. She said she'd gone to hire someone to clean their windows. The janitor at the mill where Sally worked lived in the house. He did odd jobs for Sally's mother. Jesse and Sally cursed each other, the screen door between them. A crowd gathered. Two police officers drove up. Jesse walked back to Bobby's car, and Bobby told him to get in, that he was taking him home. Jesse had been drinking, and Bobby says he was afraid of what Jesse might do. Jesse said he wasn't going anywhere, but he got in and Bobby drove off. Sally and the janitor were fired from the mill. Three weeks later, Sally and Jesse split up. They signed a legal separation. In it, Jesse promised to give Sally $12 in child support every Friday. She took the furniture and Gene, and moved into a duplex in East Winston-Salem. He took the 1954 Buick and moved back home with his mother a couple of miles away. Now I'm the man of the family, Gene thought. He was 10. The Man in the Blue Car Gene heard Sally crying in her bedroom. She was talking on the telephone, but hung up when he walked in. He asked what was wrong. Nothing. He persisted. Sally said she was dating someone and he wanted to break up. His mother had a boyfriend and Gene didn't even know it. So that's why he had spent so many weekends at Aunt Goldie's house. She said the man was worried that Gene wouldn't approve of him. Gene picked at his mother until she told him why. He's colored. Gene couldn't believe it. A colored man. It was 1961, and black people weren't allowed to drink from the same water fountains as white people. They weren't allowed in the same restaurants. It was against the law for black and white people to marry. You could go to prison for up to 10 years. Gene asked Sally if she loved the man, and she said she did. Somewhere in those few minutes, he decided maybe it was OK. If his mother loved this man, he couldn't be all that bad. One night not too long after that, Sally said the man wanted to give Gene a football. She told him to go to the corner, turn right and keep walking. The man would drive by and throw him the ball. It wasn't safe for him to be seen at their house. It was getting dark. Gene walked to the corner, turned right and kept walking. A blue '59 Chevrolet Bel Air slowed down beside him. Behind the wheel sat a thin dark-skinned man with short-cropped black hair. The man threw the football. Gene caught it. The man drove off. Sally and Tuck in Love His name was Cornelius Tucker. From that night on, for the rest of Tuck's life, Gene called him "Secret Friend." Tuck never came into their house. He'd drive by, usually after dark, honk the horn once and drive off. Sally and Gene would walk around the corner to where he waited. Most nights, they went to Tuck's house. He was 40, nine years older than Sally, separated from his wife, with two sons and a daughter. He was the man Sally was visiting on 9 1/2 Street, the janitor at the mill. They'd spoken in the halls, got to talking on breaks and had fallen in love. Sally seemed happy with Tuck. He quit drinking. He didn't yell. He listened when she needed to talk. Some nights, Tuck read them the Bible. Some nights, they watched "The Andy Griffith Show" on TV. Other nights—the ones Gene liked the best—Tuck drew a circle with chalk on the floor and played marbles with Gene until bedtime. Gene slept on a cot in the hall until they went home. Gene and Sally never stayed overnight at Tuck's house. A few times they went to a drive-in theater in Pilot Mountain, 30 miles away, once to see "Imitation of Life," about a black girl who rejects her mother and passes as white. Other nights, they cruised around Winston-Salem, Tuck and Sally up front, Gene in the back. After dark one evening, Gene says two white men pulled beside them at a stoplight on North Cherry Street and honked their horn. They called Tuck a n----- and told him to pull over. When Tuck drove off, they followed him across town. Gene remembers Tuck sitting him down for a talk later that night. "People don't look at anything but skin color," Tuck said. "They don't see that I love your mother. They don't see that she loves me. It's wrong to hate someone because of the color of his skin," Tuck said. "But people do." 'It's against God's law' On June 16, 1962, Tuck rushed Sally to City Memorial Hospital. She was gong to have a baby. Tuck didn't go into the hospital. Friends say he was afraid to. Sally was afraid to give her name, afraid that after the baby was born, and people realized the father was black, that someone might hurt the baby or hurt Tuck. She signed in as Mrs. Gladys Spainhour. Sally knew someone nice named Spainhour. She told her sister Goldie Creson to ask for her by that name if she called, and told Goldie not to visit. Goldie couldn't understand why Sally was acting so peculiar. The whole time she was pregnant, she wouldn't tell Goldie who the father was. Goldie asked time and again, and says she got the same answer: He was a truck driver and Goldie didn't know him. After Sally went home from the hospital, Goldie went to see her. Sally held the baby, a boy named Randy. The shades were drawn in the living room and it was so dark, Goldie never got a good look at him. A day or so later, their sister Blanche confronted Goldie: Why hadn't Goldie told her that Sally's baby was black? Goldie went back to see for herself. The baby was the color of light brown chocolate, with kinky black hair. Lord, what are you going to do, she remembers asking Sally. "I'm going to keep him." Goldie was so upset, she couldn't think straight. She said goodbye and walked away. He husband, Ed forbade her to go back. It was horrible for a white woman to be with a colored man, he told her. It wasn't something their three boys should ever witness. Goldie sometimes telephoned Sally when Ed left the house, and they occasionally ran into each other downtown, but the two sisters never went inside each other's homes for nearly 20 years. Everyone in Sally's family cut her off. Even her big brother, Bill, who often lent Sally his car, who took Gene to the first race at Charlotte Motor Speedway, the World 600 on June 19,1960. Bill seemed angriest of all. Bill told Jesse about the baby and then the Cheeks wouldn't have anything to do with Sally, either. She might as well have been dead. Gene says his grandmother, Sallie Cheek, explained why she thought it was wrong for Sally to be with Tuck: "You don't see a white bird or a black bird together. You never see a bluebird or a robin. It's not natural. It's against God's law." Shots in the Dark Sally and Tuck kept their separate homes, but saw each other nearly every night. Tuck worked as a house painter and gave Sally $20 a week to help support Randy. Gene adored his baby brother. When he tickled him his whole face laughed. Gene took care of Randy on Saturdays while Sally stocked shelves and sold cosmetics at Kress' five-and-dime store. He could coax him to sleep when no one else could. He rubbed Randy's tiny eyelids until they became so heavy he couldn't keep his eyes open. The last thing Randy saw before falling asleep many nights was his big brother's face. One night, Gene woke up hearing gunshots. He heard men yelling in their front yard. He drew the curtain from the window at the top of the front door. Yellow and red flames licked the darkness. A cross was burning—pieces of wood wrapped in rags and nailed together. It seemed shorter than he was, maybe 4 feet tall. Sally called to Gene in a loud whisper from the kitchen. Gene was scared, but he stuck by the door, staring outside. He couldn't see beyond the cross. Were the men who yelled and fired their guns still out there somewhere? They couldn't call Tuck. They couldn't afford a telephone anymore. They were all alone that night. After the cross burned to the ground, Gene went back to bed. In the morning, a pile of gray ashes littered their yard. Fighting Over Child Support Sally took Jesse to court six times, records show, trying to collect child support for Gene. Every time, Jesse promised to pay. Every time, he broke his promise. The first time, in November 1961, a judge ordered Jesse arrested. He sentenced him to a six-month prison sentence, but agreed to suspend it if Jesse paid the weekly child support. Jesse was brought back to court in July for not paying, again in September, and again in January. He agreed to give Sally $15 a week to catch up. But the last time he gave her money was on Jan. 29, 1963, and it was only $10. Sally was so stretched for money the housing authority sued her for $11.20 in back rent. By August, Jesse owed $413. Judge E.S. Heefner, Jr., said there was no excuse. Jesse was making $36 a week building and installing windows for Aluminum Awning Co. Heefner ordered him to prison. Jesse appealed and stayed free on bond. Still he didn't pay. On Oct.11, a sheriff's deputy arrested Jesse and took him to court. The judge said Jesse could avoid prison if he paid $200. Five days later, Jesse petitioned the court to take Gene away from Sally. He claimed she wasn't fit to be Gene's mother. 'In the matter of Gene Cheek' People who knew Jesse said he never got over Sally. She was the only woman he ever loved. He kept his wedding ring in a bureau drawer until the day he died. He telephoned her, not to say anything, just to hear her voice. He parked his car across from her house, sometimes across from Tuck's house. It was hard enough that Sally didn't love him anymore, but worse, by his way of thinking, that she had left him for a black man. A subpoena summoned Sally to court, and ordered her to bring Gene. She told him they were going to collect the money Jesse owed. Sally never told Gene that she knew it was a custody hearing, and Gene always thought she had been tricked into bringing him to court. Goldie says Sally told her she wasn't worried about the hearing. She was a good mother; no one would take Gene from her. Jesse hired an attorney and they called several witnesses. Sally represented herself. The only person with her was Gene. She left Randy, who was 17 months old, at Tuck's house. Tuck wouldn't risk going into court with Sally. He had violated an unwritten code of racial conduct by having a child with her and it would be dangerous if he tried to defend her in public. Judge Heefner's order, "In the Matter of: Jesse Eugene Cheek," summarized what happened. First on the witness stand was John Shell, a lifelong friend of Jesse's who lived next door to Sally. Shell testified that Gene shouldn't be living with Sally because she was seeing a Negro man. He said the man came by Sally's house almost every evening between 7:15 and 8 and tooted his car horn. Within a short time, Sally would leave her house and walk to the far end of the street. Sometimes she took Randy and Gene with her. Other times she left Randy with Gene. Shell said he saw Sally use the public telephone down the block, and afterward the Negro man would drive to her house. He saw her get into the car with him. Some nights she returned home as late as midnight, Shell's wife testified. She said Sally wasn't fit to have custody of Gene, that "she is mixing color." Next on the stand was Jesse. He testified about the afternoon he found Sally at Tuck's house on 9 1/2 St. Jesse didn't want Gene living with her, but he said he couldn't take care of him. He was epileptic and alcoholic. He said he would support Gene in a proper home. Sally's brother Bill told the judge that neither Sally nor Jesse was fit to have custody. He said it would make Gene happy to be taken away. "I've done right by Gene," Sally testified. She said she'd given him love and care, and that she'd worked hard without help from Jesse. Sally lied about her relationship with Tuck. She said Tuck wasn't Randy's father, that Randy's father had died. She said she couldn't remember where or when Randy was born. Gene was the last witness. He testified that he wanted to stay with his mother. He said the judge had no right to take him away. Judge Heefner gave Sally a choice: Give up the baby or give up the boy. Sally couldn't choose between her two sons. Heefner ruled that Gene should be placed into the custody of the child welfare department. He wrote in his order: "The mother, Sally Anderson Cheek, is not a fit and proper person to have custody of her son, Gene... The moral conditions in the home are unfit and she is training him to defy any and all authority, and is failing to provide for his proper discipline. It is now, therefore, ordered and adjudged that the custody of Eugene Cheek is forthwith removed from the mother." Sally appealed the ruling, but never paid the $9 filing fee to pursue it. Sent Away, Heartbroken Gene spent two nights and three days locked in the youth center. He was 12 years old, and all alone. He felt so angry, he could have punched his father, so heartbroken he could have curled up in his mother's lap. He cursed. He wept. He slept. A stranger shoved plates of food through an opening in the door. On the third day, a social worker took him to a foster home. Gene didn't like his foster parents. They stood in the way of seeing his mother. He spent as much time away from their house as he could. He often left early for Hanes Junior High, ate a doughnut at the diner and put a nickel in the jukebox to hear the hit song, "I Want to Hold Your Hand" by the Beatles. The welfare department allowed Gene one afternoon a month with Sally. That wasn't enough. He skipped school to see her. He rode the bus or biked across town. Sally fussed at him for playing hooky. But he could tell she was glad to see him. It was obvious Gene would never feel a part of that foster family, or any foster family. His social worker decided he might do better at Boy's Home in Columbus County, 150 miles southeast of Winston-Salem. Most boys were sent there because of problems at home—alcohol, abandonment, poverty. They had committed no crime, but had no place to go. "Gene is highly dependent and emotionally attached to his mother," the social worker wrote in an application. "The problem of his adjustment in Boys (Home) is obviously going to be the same as the problem of adjustment in a foster home. That is, he cannot get along without constant contact with his mother." Gene didn't want to go that far from home. Sally didn't want him to go, either. Jesse signed the authorization papers. The Hurt Never Went Away It was a crisp, clear day, Sept.18, 1964 when the social worker drove Gene to Boys Home. He had never seen Spanish moss. It hung from the branches of pecan trees in an eerie sort of way, and Gene felt as if he were in a foreign country. He wanted to cry, but he was 13 years old and he didn't want anyone to see him. He walked into a cottage. There was another boy inside. The boy stared at Gene, then said something Gene didn't like. Gene said something smart back at him. The boy popped Gene in the mouth. Gene popped him in the nose, knocking his glasses to the floor. It was the first of many fights. Boys Home was built on the shore of Lake Waccamaw. There were six cottages, four bedrooms each, four boys to a room, one counselor to a cottage. The were no doors on the bedrooms. No locks on the front doors. Gene lived there five years, and many nights he cried himself to sleep, thinking about Sally and Randy. The hurt and anger never went away. He didn't study much, and the D's and F's on his report card showed it. He took his turn mowing grass, feeding cows and pigs, clearing land. He toured the state with the Boys Home choir, taking the spotlight as soloist on "Edelweiss," "Blowin' in the Wind" and other popular songs. He played linebacker on the Hallsboro High School football team, guard on the basketball team, catcher on the baseball team. He threw shotput and discus on the track team. By his senior year, he stood 5'11" and weighed 170 pounds. Gene grew close as a brother to some of the boys. But no one ever asked him why he was sent to Boys Home, and he never asked anyone that question. It was something you just didn't do. Every Friday, Gene got a letter from Sally with $2 in it. He never heard from Jesse. He was allowed home 10 days at Christmas and 10 days in June. A few other times, he ran away and hitchhiked to Winston-Salem. Sally and Randy were living with Tuck, then, in a black neighborhood. Tuck made golf clubs by nailing together two pieces of wood, and he and Gene and Randy would play until dark, sinking balls into holes they dug in the backyard. Then they'd sit around the kitchen table with Sally, eat and talk. Some nights, Gene drew a circle with chalk on the carpet, and played marbles with Randy, the way Tuck had played with him. Gene felt as if he was part of a real family. It made him happy. But eventually the police would come with a bus ticket and send him back to Boys Home. The counselors spanked him with a wooden paddle and grounded him for a month. In 1969, Sally rode a Trailways bus to Lake Waccamaw to watch Gene graduate from high school. She told him how proud she was of him. She had dropped out of high school after her sophomore year. Gene was proud she made the trip. He was 18, no longer a ward of the welfare department. He borrowed the Boys Home station wagon and drove Sally back to Winston-Salem so she wouldn't have to ride the bus. Running from His Past Gene joined the Navy to avoid being drafted into the Army. He trained as a weatherman and spent most of three years aboard the USS Iwo Jima off the coast of Da Nang in Vietnam. The carrier's helicopters flew Marines in and out of the war zone. Gene stayed on ship, junior man in the weather office. He didn't take orders well. He distrusted authority figures. He partied too much. Back in the states, he fell in love with a woman from San Diego. They married in 1972 and raised three children. Gene made sure his son and daughters knew he loved them. If Jesse had loved him, he would have offered him a home when the judge sent him away. Gene went to all of David's baseball games. To all of Roxanne's church plays. To all of Jennifer's band performances. Still, he was afraid to get too close to anyone. The anger from childhood burned inside. He says he could never settle down. He assumed that life wasn't good because of where they were. It would be better somewhere else. He convinced his wife that if they moved he could make more money and they would be happier. Within a few years, the happiness always wore off. The moved again—from San Diego to Winston-Salem, back to San Diego, to Winston-Salem again, back to San Diego, then Wenatchee, Wash., then to Newton in Catawba County. Gene worked as a painter, a quality-control inspector, a satellite dish salesman, a car salesman, siding salesman. If something went wrong, he looked for a new job. He never confronted what troubled him. He says he never realized he was running from his past. Gene Confronts His Father In October 1987, Gene got a telephone call. Jesse was dying. Gene took off work to sit with his father in the hospital. They had seen each other only a half-dozen times in the 24 years since the custody hearing. Jesse had lost his left eye to cancer. He was so emaciated, his bones stuck out, his skin sagged. Gene wanted Jesse to apologize for what happened. He needed him to admit he'd been wrong. He hoped they could reconcile. "If you've got anything you need to get off your chest, now's the time to do it," Gene says he told Jesse. "If you've got any peace to make with me, now's your chance." "I'm fine, son." 'What would I be like?' After Sally died, on April 30, 1995, and the past could no longer hurt her, Gene decided to find out about his custody case. He wanted to write a book. It might not help him, or change any racist minds, but he felt compelled to tell what happened. Gene procrastinated for five years. Finally, in February, he called Boys Home. A month before his 49th birthday, an envelope arrived, 15 pages of documents inside: medical records, a report card, a psychologist's evaluation. Buried in a summary from his social worker was the reason the judge took him from Sally: "Mrs. Cheek has been carrying on a continued relationship with a Negro man by whom she has had a child." For the first time in his life, Gene saw in writing why he was taken from his mother. He started to cry, but choked back the tears and cursed instead. All the old anger rushed at him. He always suspected that everyone from the judge on down would have tried to hide the real reason because it wasn't reason enough.

"It broke my heart. I looked at that report and I thought, 'Where the hell is that kid?' They saw a tremendous amount of potential in me. I could have been anything I wanted to be had I not spent most of my life fighting authority and the establishment. And that stems from Nov. 18, 1963, when they carried me out of that courtroom. My entire life was dedicated to getting even. "I ask myself: 'What if?' What would I be like? What would my life be like if they hadn't taken me?'" (Leland's series won first place for news features in the North Carolina Press Association competition.) | |||||||||||