Anne Hull and her editor decided it would make a good story if she stayed with the women recruited to work in North Carolina from the time they received the telephone call to leave Palomas to their return after six months shucking crabs. In this excerpt, Hull describes the women as they leave their Central Mexico village: The job recruiter had left specific instructions for the women going to Daniels Seafood: Be at the bus station in Cuidad del Maiz by 6 p.m. on Friday. Juana spent her last hours baking corn bread in her outdoor kiln. Ana Rosa wrapped warm gorditas in a plastic garbage bag. It would be a long bus ride to North Carolina, and they did not want to go hungry. Juana's youngest sons, ages 6 and 8, played soccer in the sandy courtyard, unable to bear the sight of their mother's suitcase near the door. At 4:30, Juana called the children inside. Her long hair was still wet from her shower. The van was due. She asked everyone to kneel. Ana Rosa knelt on the bare concrete floor and joined hands with her brothers and sisters. The children's voices were high and metallic, but it was Juana who could be heard above all. She asked one favor of God. "I leave them with you, Lord," she cried, her eyes closed. "Gracias, Señor Jesus, gracias. Gracias, mi padre." Tears rolled down Ana Rosa's smooth cheeks. The 11-year-old, Claudia, brushed her eyes. Eduardo looked at his bare feet. When the van honked outside, Juana was the first to stand. The oldest boy loaded the suitcases. At the patio gate, near her rosebush, Juana hugged the children goodbye, saying each of their names aloud. "Alejandro." "Claudia." "Maria de los Angeles." "Tomas." "Lorena." "Eduardo." Instinctively, Juana hugged her youngest child once more. As she boarded the van and pulled the door closed, Eduardo's screams shook her. "Mami, mami!" he cried. A burro at the gate began braying, and Eduardo flailed at the animal before throwing himself on the ground, sobbing. "Hurry!" Juana begged the driver. Her shoulders heaved. Someone reached for the roll of toilet paper jammed into the dusty dashboard. Ana Rosa passed it to her mother, but first wiped away her own tears. The van pushed through the streets of Palomas. Three suitcases were waiting in front of a house across from Señor Herrera's store. As the driver honked, the door opened, and eight family members spilled out into the street in a jumble of hugs and goodbye's. Delia and Ceci Tovar were in the middle. Their mother hung back. "The rich need the poor and the poor need the rich," she often said, justifying why Mexicans were always saying goodbye in the name of a better life. But she whispered no great words of wisdom into her daughters' ears now. When she held them tightly, one last time, tears streamed down her cheeks. The van sagged with the weight of 18 passengers. Suitcases were shoved in corners and piled to the ceiling. Just lifting a hand to wipe a brow was impossible. Sweat trickled between breasts. The air was thick and sweet from body odor, hard to breathe.

The dashboard radio was nothing more than a rusted shell of antique parts, but the driver leaned forward and twisted the knobs, desperate to break the silence. No one spoke as the van picked up speed. An accordion canción played. Delia turned around once, to look back, but Palomas was gone.

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073511935/535056/Una_Vida_MejorGCoA_Better_Life_p1.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (94.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073511935/535056/Una_Vida_MejorGCoA_Better_Life_p1.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (94.0K)</a>

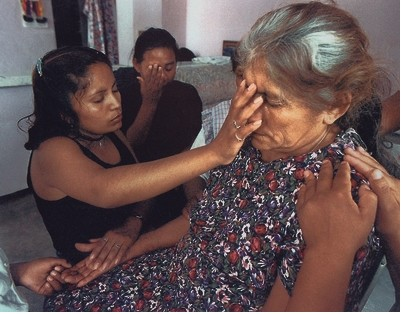

| Joshua Dautoff, St. Petersburg Times | Prayer Before Leaving | Anna Rosa, 19, and her grandmother pray for a safe journey before Anna leaves for North Carolina in search of una vida mejor. |

Writing Long: Anne Hull on "Una Vida Mejor" Hull's three-part series on the young Mexican women ran more than 15,000 words. Here are some of her thoughts about how she handled the reporting and writing, and what she learned from the project: Lesson one: Certain stories require a time investment. When I first started reporting "Una Vida Mejor," my editor and I thought I would go to Mexico, travel by bus with the women to North Carolina, and then hang around for a week or two to observe their indoctrination as crab pickers. We quickly realized this story would be all the more powerful if we could follow an entire six-month crab season. Al1 stories need endings, and "Una Vida Mejor" begged for one: Would Ana Rosa and the other women from Palomas ever fit back into their traditional lives in Mexico, their pockets full of cash, their suitcases stuffed with Wal-Mart jogging suits? How could we tell this story if we didn't know how it ended? Lesson two: Read. I read and re-read passages from Melissa Fay Greene's Praying For Sheetrock to see how she paid attention to small details, and to try to break myself of conventional journalistic structure.

<a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073511935/535056/Una_Vida_MejorGCoA_Better_Life_p2.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (70.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073511935/535056/Una_Vida_MejorGCoA_Better_Life_p2.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (70.0K)</a>

| Reporter and Source | Anne Hull met some of the long-time crab pickers. |

When the group arrived at the Outer Banks. One of them, Mary Tillett, helped Hull with background. The older crab pickers were retiring and were being replaced by the Mexican women. Lesson three: Organize notes throughout the reporting process. I had a tower of notebooks, not counting documents and stats from federal agencies. Figure ways to remind yourself what's in each notebook. (For example, scribbled on the front of one notebook: "night Ana Ross got kissed/Mickey at church/crabbing with Mickey on cold day.") To really organize, number each page in a notebook and make an index of key moments, facts, and quotes within that particular notebook. Lesson four: Find off-camera "experts" who will likely not appear in the story but will act as your guardian or teacher. It's tempting to put these sources in the story, but their role is often much more valuable backstage. Lesson five: Witness as much as possible. Experience what those you are writing about experience. This can mean uncomfortable accommodations, no toilets, or four-day bus rides across 2,500 miles. Suffering by proxy is no good; besides, you miss all the details, and later, the license to really tell the story. Lesson six: On long stories or projects, allow—beg for—time to re-draft. Do not leave yourself four weeks to write a story you have spent five months reporting. Start writing as early as possible. Signal to your editor you want time to have the story superbly edited so there's no hysterical crunch at the 11th hour. (There will be anyway.) |