Thomas French describes the way he went about gathering information for his seven-part series about Largo High School : Getting Started We were open with everyone from the start about who I was and what I was doing. To gain access to the school, I first had to win permission from top school-system officials, then from Largo 's principal, then from the entire Largo faculty. My presence was announced over the P.A. system, at the parents' Open House, in the school newspaper and in dozens of classrooms. Plus, I was constantly scribbling in my St. Petersburg Times notebooks. Still, I do feel that at least some of the kids opened up to me. I don't harbor any illusions that they shared every secret, but many of them came to feel fairly comfortable talking about extremely intimate details of their lives. Why? I suppose it helped slightly that I didn't dress myself in such a way as to stress my age. I wore my Nikes and stayed away from ties, but unless I'm interviewing a judge or a tight-lipped business exec, I always wear my Nikes and no tie to work. With the senior honors students, it also helped that I repeatedly explained to them that whatever I wrote was not going to appear until long after they'd graduated, which meant they felt much more free to speak truthfully about the rules and the principal and the system. When it came to finding successful students to write about, I deliberately looked for seniors with this in mind. Avoiding Judgments Through it all, the most important thing was that I tried to be myself, to be open, to not judge, to let my genuine curiosity and interest show through. I've always found that most people, except for movie stars and professional athletes, who would charge you for their spit if they could, appreciate it when someone takes the time to find out about their lives. I liked these kids—liked them a lot—and though I didn't make a big deal of it, I think that affection was obvious. Again, I also avoided passing judgment, giving lectures, allowing anything even suggestive of adult disapproval to cross my face. I just tried to understand them and tried, as best I could, to remember how confusing it was to be 16. Having said all that, there were clearly some kids who opened up more than others. Mike Broome, for instance, was so eager to thwart analysis that I would interview him for hours without getting one piece of insightful information. Same thing with Jaimee Sheehy. With them, I learned more from interviewing their families and friends, and especially from just hanging out with them. With all of the kids, as with everyone I write about, I found that some of the most revealing stuff just came from turning as invisible as I could and keeping my eyes and ears open, watching them interact with their friends and teachers. (Or not interact, which was also revealing.)

French says he had struggled to find the best way to approach a story about schooling, first writing about kindergarten, then fourth grade students, then about a new teacher's first day in high school. Searching for a Frame As the school year began, I began searching for some kind of frame—a process, a problem, a story—that would yield itself to an unfolding narrative. In pursuit of that frame, I wrote several one-shot stories. What I found was that teachers were dealing with the same problem from day one of kindergarten through high school. Namely, how to reach their students and hold onto them. How to connect with them. How to prevent them from eventually joining the tens of thousands of kids who drop out of Florida 's public schools every year. So that was my frame. That was going to be the central engine driving my story. Is Mike Broome going to let his teachers inside that emotional fortress? Or is he going to throw his life away and drop out? What about Jaimee? What about everyone else? Are they going to make it or aren't they? It's a little bit like a war story. Who's going to live? Who's heading home in a body bag? Writing for Readers For the maximum drama—and also, so I could deal with people old enough to tell me whether they were comfortable with me writing about them—I decided to go to the front lines of the battle, to high school, where teachers wage a last-ditch attempt to keep their students from walking out the door. From the start, however, I knew that I didn't want to just write about dropouts. I wanted to follow successful students as well, to examine their lives and backgrounds and try to illuminate why they were making it when so many others were not. But I also wanted to draw a larger portrait of high school at the end of the 20th century. What's it like? How is it different from when we went to school? How is it the same? (So readers wouldn't feel as though they were wandering a moonscape—so they wouldn't have the luxury of removing themselves that way—I deliberately balanced the shocking and startling stuff with some archetypal scenes and experiences that I knew almost everybody would remember and connect with emotionally.) More than anything else, I knew I wanted to focus on the stories of a handful of kids whom the readers would care about and want to know more about—kids who would keep people reading. Depth Reporting I started hanging out at Largo High in early October—it took the first six weeks of school to get all the necessary clearances—and I was there almost every day for the next four or five weeks. After that, I went back less frequently, say maybe once on twice a week, until the last six weeks of school, when I was there almost every day again. Once the school year was over, I spent the next several months doing follow up interviews—I'd only made my final picks on which kids to focus on around April—and tried to organize my notes, which included 43 reporter's notebooks and hundreds of pages of interview notes on 8 1/2 x 11 paper. Story Lines By then, of course, I'd found several other story lines to weave into the tapestry. Will YY follow her heart and become a writer, or will she give in to her parents' pressure and study math? Will she and her three girlfriends find a way to hold onto their friendship through their senior year? Will Andrea Taylor win Homecoming Queen? Will she be able to get together with John Boyd without destroying her friendship with her childhood friend, Alyma? Will John Boyd survive the drug wars in his neighborhood? Will he get caught with his gun, or hurt someone with his gun, and thereby ruin any chance at a college scholarship? Will Jaimee Sheehy's mother find a way to get through to her before she winds up dead in a car wreck? I began writing in early August and didn't finish the writing until after the series had begun running in the newspaper. (Madness.) All along, I was turning to other writers, asking them to read drafts, bouncing ideas off them, begging them to tell me everything was going to be all right.

French was inspired and depressed by what he saw in his months with the students—inspired by many of the students, depressed by what he says is society's "addiction to magical solutions and pretty slogans." Some Afterthoughts How did I feel about all that I saw inside the school? Sometimes I was left with a terrible sense of emptiness and gloom. Other times, the irreverence and energy of the kids made me feel extremely hopeful. Personally, I felt that most of the problems I was seeing had more to do with the world outside the school than the school itself. When people ask me now what's wrong with our schools, I'm always tempted to hand them a mirror. I came away feeling that the school was doing a remarkable job of salvaging as many kids as possible, especially given the lack of support coming from the society outside and given how many problems the teachers were dealing with. This country loves to talk about how important education is—every president says he's the "education president"—but the truth is that this country doesn't give a damn about schools and hasn't given a damn for many years. In Florida, for instance, our schools are partially funded by the lottery, which is to me a very revealing contradiction. The idea behind a lottery is that the best thing that could ever happen to you would be for you to get lucky and suddenly strike it rich for nothing. This is a poisonous notion, and one that undermines every belief behind education: that some goals are worth years of work; that not everything of value can be measured in dollars and cents; that work is its own reward; that thinking and learning and growing are their own rewards.

Here is the beginning of French's seven-part series about Largo High School : Show & Tell The files in the front office would have you believe the two of them go to the same school. And technically speaking, this is correct. They both walk the same long halls, weaving through the same crush of teenage bodies. They sit in classrooms only a hundred yards from each other, trapped behind weathered desks scrawled with the same declarations of love and lust. They rail against the same mind-numbing rules, make cracks about the same principal, sneak off the same campus at lunchtime, just to escape whatever's being dished out in the cafeteria. The truth is, though, the two of them don't go to the same school at all. Even if they brushed shoulders in front of their lockers, they probably wouldn't notice each other. They are invisible to each other. She is 17, a senior, on her way to college and a future positively brimming with possibilities. She has a nickname that sounds like a double question—YY, people call her—a permanently tangled mess of brown hair and an alarming shortage of eyelashes, which she tends to pull on whenever her nerves get frayed, which is almost every day. The pressures that weigh upon her are immense. She is vice president of the National Honor Society; president of the Latin Club; a member of Mu Alpha Theta, better known among the masses as the math honor society; co-editor-in-chief of the school newspaper; and a starter on the school's academic quiz team, which happens to be the reigning county champ and which is counting on her once again to smother the buzzer like mousse on a prom queen. As if that's not enough to make a girl sketch out and go psycho—and YY will be the first to admit it happens from time to time—she is also a buffet gal at the Belleair Country Club; an older sister and part-time caretaker of three infinitely younger brothers; a flutist who performs every Sunday at her church; a free agent in the savage arena of dating (no one has asked her out for centuries); and a high-ranking member of the most exclusive clique on campus, which can be a full-time job unto itself. Her grade-point average, meanwhile, hovers somewhere in the upper reaches of the atmosphere, where it must stay if she wants to keep the scholarship her parents are counting on for next year. At the moment, she is sitting at the back of her Latin IV class, snacking on M&Ms—in brazen defiance of school policy—while she quietly translates, from the original Latin, an oration Cicero delivered to the Roman Senate in 63 B.C. against some poor stooge named Catiline. "How're you doing?" asks her teacher. She sighs. "Oh, fine. Cicero 's boring." The teacher smiles. "He is boring." "He's very long-winded. All he says is, 'Get out of town, Catiline! And take all your followers with you!'" Still, YY knows that Cicero is important, because she knows that eventually she will be tested on him and because she knows that tests are not a thing to be taken lightly. Not by anyone who wants to become anything. Dutifully, without a word of prompting, she returns to the book and her notes. Her teacher, standing at the front of the room now, assures the class that what they're learning is important. They will use Latin, she says, for the rest of their lives. Not far away, in a cluster of classrooms known as the pod, a 14-year-old boy named Mike slouches through another day of earth science. He is a freshman, well on his way to failing all his classes and to relegating himself to a lifetime of diminishing possibilities. He's not stupid. If he wanted, he could do most of his work in his sleep. Occasionally he does just that. He'll sit at his desk with his head down and eyes closed, and a teacher will call on him, and he'll look up, give the correct answer to whatever's been asked, then return to his dozing. But not today. Today, like so many days, he is angry. Don't ask what he's angry about: Even if he could explain it, he probably wouldn't tell you. |  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073511935/535072/A_Year_at_School_p1.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (14.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073511935/535072/A_Year_at_School_p1.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (14.0K)</a>

| Maurice Rivenbark, St. Petersburg Times |

|

He has light blue eyes that burn, a scraggly collection of chin hairs that may someday qualify as a beard, and the fervently indifferent air of someone fighting to convince himself that the world has nothing interesting left to show him. He belongs to no club or organization, except perhaps the congregation of metalheads, skateboard cowboys, Nintendo junkies and other dispossessed souls who meet every day on the auditorium steps. He wears an earring shaped like a skeleton smoking a joint. His right arm bears a homemade tattoo that shows a symbol for anarchy. His jeans are marked repeatedly, in dark black ink, with the letters "FTW." If there's any doubt about what these stand for, he'll be glad to translate. "F-k the world," he'll say. At this moment, he is sitting in the corner of the classroom, ignoring his teacher as she tries one more time to prod him into joining the rest of the class. She likes this kid. Beneath his anger, there is something special about him. Something promising that goes beyond the fact that he so obviously has brains. His other teachers sense it, too. They can see it when his guard is down, flickering momentarily behind his eyes. Maybe he's lost. Maybe he's been in a tailspin for so long he doesn't know how to pull out. So the teacher keeps trying. She brings him a book and opens it for him. She finds the right page. When he still refuses to work, she says that perhaps he shouldn't come to class tomorrow. "Mike," she tells him. "This is a waste of your time."

Here is the beginning of the seventh installment of Thomas French's series about Largo High school : Solitaire Bodies bumping past one another in the hall. Fists pounding on the walls, if only for the sake of making noise. Inside the pod, the bell for third period has just rung, and Mrs. Frye has handed her critical thinking class a list of unfinished sentences: You are like an untraveled path when...

You are like starlight when...

You are like a mountain when...

You are like a flower when...

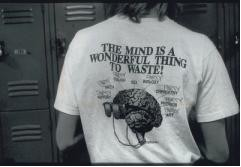

" Wayne," she says, looking at one of the boys, "you are like a flower when what?" He says nothing. "What is a flower? How would you describe a flower?" "Ugly," he says. " Wayne, finish the sentence. You are like a flower when..." "It smells." Mrs. Frye turns to a boy wearing a Metallica shirt that shows someone writhing in an electric chair. A boy who has not bothered coming to her class in many days. Mike Broome scowls. "I ain't a flower." "I didn't say you were a flower." "I don't feel like no flower, either."  <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073511935/535072/A_Year_at_School_p2.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (12.0K)</a> <a onClick="window.open('/olcweb/cgi/pluginpop.cgi?it=jpg::::/sites/dl/free/0073511935/535072/A_Year_at_School_p2.jpg','popWin', 'width=NaN,height=NaN,resizable,scrollbars');" href="#"><img valign="absmiddle" height="16" width="16" border="0" src="/olcweb/styles/shared/linkicons/image.gif"> (12.0K)</a>

| Maurice Rivenbark,

St. Petersburg Times |

| Kim Frye, a young teacher with a soft voice and deep reservoirs of patience, has this fantasy. Sometimes, when her students are like this, she imagines walking into class wearing a hockey mask and carrying a chainsaw. She sees herself ripping out the cord, kicking the saw into an ominous growl. She sees the looks of fear on the kids' faces. She even hears the words she'd use on them: "Now you're going to pay attention." |

But now, facing the indifference of Mike Broome, Mrs. Frye does not have the option of waving a chain saw. Not unless she wants to wind up on the 6 o'clock news. So she moves on, handing our another worksheet. Mike puts his head down on his desk. "What's wrong?" she asks him. "I'm tired." "Why are you tired?" "I don't know." "Why are you here?" "I don't know. So I can get my license." He tries to put his head back down, but Mrs. Frye won't let him. "You're not going to sleep." "Fine, I'll just go home." He gets up, moves toward the door. "I'm fixing to leave," he says. Mrs. Frye is up front now, working with another student. She's trying to ignore Mike; she has no time for this. Maybe a month or so ago, when there was still a chance for Mike to turn it around again. But not now. Not on this Thursday in early May, when there are only a few weeks left in school. "Can I leave?" he asks. No answer. "Can I leave then?" He storms out, slamming the door as he goes. Outside, Mike tries to walk off his rage. He's almost running. He goes from one end of the school to the other, finally ending up on the auditorium steps, where he lights a Marlboro. "I just didn't feel like sitting in that class," he says. "I just didn't see no use in it. I've already failed this year." He's right. He could file an attendance appeal, but he's skipped so many days there's almost no way the appeal would be approved. "What's the point?" he says. So now he's destroying anything tangible he'd managed to build early in the semester. His grades. His credits. His chances of passing any of his classes. He's tearing it all down, kicking and clawing and stomping on even the smallest blade of hope. His teachers have tried. But sooner or later, there comes a point where it's up to him. It's like someone was saying one day in the pod. Teachers, this person was saying, cannot save anyone. They can't just throw their students a rope and lift them out of whatever hole they've fallen into. The kids have to grab the rope and put one hand over the other and start climbing. Mike has decided to stay deep inside his hole. He sits on the steps, smoking his cigarette and feeling the wind in face. "I've never skipped a day of school in my life," he says, serious all of a sudden. "I've never skipped a full day."

|