(See related pages)

Crumbling Buildings Less than $3.5 billion is being spent a year to repair and replace school buildings. The General Accounting Office estimates the total needs at $112 billion. Children are being taught in trailers and are bused to nearby communities as the population increases and voters turn down bond issues to build new school buildings or repair old ones. The school-age population, now about 52 million, is expected to reach 56 million in 2004. In Ohio, the Akron Beacon Journal found school buildings in serious disrepair. Instead of fixing them, the state legislature exempted schools from parts of the building code. Packed Classes Overcrowding has become commonplace as money-starved schools find it difficult to hire additional teachers and school construction bond issues have been rejected by voters. Journalists have shown the tension in communities between retired homeowners living on limited incomes and young newcomer families with school-age children. The older people vote against the bonds that young families favor. By showing the crowded conditions in classrooms and the consequences—overwhelmed teachers, low test scores—newspapers and stations have helped alleviate some of the worst problems in many communities. Vouchers Increasing pressure is being put on state legislatures to direct tax money to parents who could then use the funds for schools of their selection. Advocates say that this would give parents choice and result in better education for all children. Opponents of the voucher system say that the result would be the destruction of the public school system. Also, they say, the voucher system would allow tax monies to be used for religious schools, a breach of the First Amendment. Among the states in which the voucher plan has considerable support: Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin. Newspapers have conducted polls to gauge community support for using tax money to support nonpublic schools, and their results and those of polling organizations indicate a majority oppose vouchers. Standards Just what coursework is required for a high school diploma? Colleges and universities required to admit high school graduates found that they were admitting high school graduates who were semi-literate and had no idea of how to do basic arithmetic. They put pressure on the high schools to tighten their requirements for graduation. Reporters have dug into the high school curriculum to see what is being taught. In response to complaints that high school graduates could not handle college-level work, many states adopted standards that students would have to meet to graduate. Some of the standardized tests seemed too difficult for large numbers of students and they, their parents and teachers protested. The passing grade of 65 was lowered to 55 and plans to end automatic promotions were shelved. Most education experts say present standards for high school graduation in most states are set at the eighth-grade level. More states (29) require physical education to graduate than require algebra (13) or biology (8). Religious Values As the Religious Right widened its political activity, its influence was felt in the nation's public schools. In a special report, the Anti-Defamation League stated, "Religion is currently entering the public school system through a variety of means, including school prayer, graduation prayer, religious clubs, religion in the curriculum, creationism, censorship, distribution of religious materials and voucher plans." The so-called wall of separation between church and state in effect keeps government out of religion and religion out of government. The Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional such practices as ceremonial readings from the Bible in the classroom and organized prayer at student assemblies, athletic activities and special events. Yet such practices exist and are stoutly defended in a number of communities. They continue until someone goes to court to challenge the breach in the wall of separation. Bills have been introduced in 12 state legislatures to permit school prayer; in 10 legislatures to allow the teaching of creationism as a science; in nine state legislatures to post the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms. Segregation Because of housing patterns, black and Hispanic students make up the majorities of students in many urban schools. In Hartford, for example, more than 90 percent of the students were in these two groups, whereas in the nearby community of Farmington, the schools had a 90 percent white student body. The differences in achievement were marked:

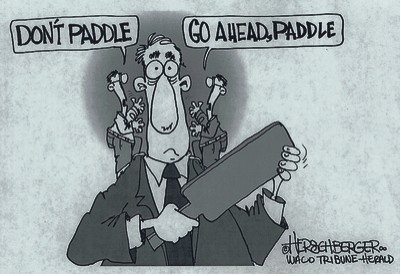

Thirty-one percent of the Hartford high school students went on to four-year colleges, compared with 76.4 percent of the Farmington students. Tests How do you test a school's performance? The reporter usually looks to test results. But some administrators say the standardized tests really don't measure a school's effectiveness. Albert Shanker, who was president of the American Federation of Teachers, said administrators would tell him "they had a new plan or policy or initiative that was making a tremendous difference. "You couldn't see any difference in the test scores, they'd say. But that was not the whole story. If I would only go into the schools, I'd see kids smiling, and I'd feel the warmth in the classroom. That would tell me a whole lot more than test scores." Shanker did not buy the reassurances. "The whole point of school reform," Shanker said, "is to have students learn more. If this doesn't happen, the experiment is a failure, no matter how happy the children, the parents and teachers—and the reformers—are." Punishment Some school systems are debating retention or establishment of physical punishment for errant students. The discussion usually pits civil libertarians against more conservative groups in the community.

Assessing High Schools The Seattle Times spent eight months examining the performance of high schools in the area. Reporters looked into everything from attendance to the grades that graduates received at the University of Washington. A total of 91 schools were examined, 66 of them public schools. The newspaper found some schools whose students excelled in academic performance, some whose students did not do well in their college freshman year. The San Jose Mercury News found that many California high school graduates are unprepared for college work. Half those admitted to the California State University system were required to take remedial English. Many of these remedial students had good grades in their high school English classes, the newspaper found. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found that nearly a third of all college freshmen drop out of college within a year, 40 percent of high school graduates need remedial work in their first year and fewer than half the freshmen graduate within a six-year period. The Daily News in the Virgin Islands found that although the Islands spend more money per pupil than most states, their high school graduates finish last on every standardized test they take. Their honor roll students in high school find themselves in remedial English and math classes as college freshmen. The newspaper found students often have no textbooks, teachers fail to show up for work, parents are indifferent, and the Education Department has lowered standards so that "even valedictorians and salutatorians must take remedial classes in college." Seventy-eight percent of high school seniors read below grade. The Omaha World-Herald analyzed test scores and sent reporters into classrooms. It found that the schools that did well had in common:

Equal Funding The disparity in tax support for the schools has led to court battles in more than 30 states. State courts have split almost evenly on the question of whether schools should be supported from local property taxes or should be supported equally from state funds. Only Kansas and Vermont have passed statewide property taxes to support their schools. The Vermont action was in response to situations like this: Richford spent $3,743 per pupil, whereas Peru spent $6,476 per pupil because of differences in the valuation of property in the two communities. These wide differences are not unique to Vermont. A school district in Texas spent $56,791 for each student, whereas the poorest school district in state spent $2,337 per student. In Montana, spending per pupil ranged from $2,650 to $9,750. Some states are experimenting with a state sales tax mandated for school expenditures. The differences in funding make for dramatic comparisons. Ramon Renteria in Texas and Sam Roe in Ohio compared the schools two girls attend to illustrate the consequences of unequal school financing. Renteria's story begins:

Roe's story begins:

| |||||||||||||||||